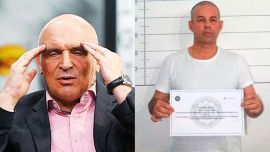

José Luis Espert, the economist who made a political career out of the slogan “cárcel o bala” (“jail or bullet”), is entangled in a web wrong-footing him against his own discourse. Documents and testimony link him to Federico Andrés ‘Fred’ Machado, an Argentine entrepreneur wanted in the United States in relation to court proceedings involving suspected drug-trafficking and fraud.

This case originated in Texas, where Machado faces trial together with his partner Debra Lynn Mercer-Erwin, who was sentenced last year to 16 years in prison on similar charges: drug-trafficking, money-laundering and fraud. Among the accounts confiscated by the prosecutors there appears a money order dated February 1, 2020: a transfer of US$200,000 made out in Espert’s name.

The money had been paid out by the Aircraft Guarantee Corp, a trust administered by Mercer-Erwin, identified as a cover for registering aircraft and – according to the charges in the United States – covering up a scheme of fraud and the contraband of cocaine disguised as transactions for the purchase and sale of aircraft.

Machado has been under house arrest in Viedma awaiting extradition to the United States, which has just been authorised by Argentina’s Supreme Court.

Never declared

The problem for Espert is that he never declared this contribution either before Argentina’s Electoral Court or in public. And nor is this an isolated incident – journalistic reconstruction of his 2019 presidential campaign shows Machado to be his chief financier.

Apart from money, the businessman also supplied logistics: a private jet used by the candidate and an armoured Grand Cherokee jeep registered in the name of a cousin, Claudio Cicarelli. In video footage circulating online dating back from that time, Espert can be seen thanking Machado for “the excellent flight” after they landed in Viedma and attended a book launch event.

The businessman’s 4x4 ended up being a protagonist in a shady episode linking Espert to Machado – in August 2019 it was attacked en route to Crónica TV channel with two stones hurled at the corner of Avenidas Madero and Córdoba downtown. Upon investigation, it was confirmed that the vehicle belonged to the businessman’s entourage. Noticias magazine revealed that Machado was the man financing the Espert campaign.

Machado’s contributions in cash and kind (aircraft and car) were never declared, as required by electoral law. According to former party colleagues, Machado’s assistance could have totalled US$700,000 or even more.

At the end of that year, things happened which would arouse the suspicions of any observer of reality – if you go looking for all Espert’s sworn affidavits and statements presented up until now, those which can be found are 2018 (incorporated into his 2019 presidential candidacy) and those accumulated since 2021 as deputy.

In these documents, a leap in Espert’s assets can be seen, dating from 2019. He bought a house of 470 square metres in San Isidro, acquired a brand-new BMW 240 coupé and closed out the year receiving farmland as inheritance in his native Pergamino. Furthermore, at the end of 2019 Espert and his wife set up the company Varianza SA, whose activities are unknown. A striking inconsistency is that in his sworn statement as deputy the company figures as having been formed in July 2020.

He was not the only one with economic changes in his life following the presidential campaign – Espert’s running-mate Luis Rosales traded in a Volkswagen Tiguan 2012 for a hybrid Toyota Rav 2020.

Contributor

Machado, 57, was born in Viedma and constructed his fortune in Florida, where he founded the firm South Aviation and a handful of aviation companies. For the US courts his business was a façade for a structure dedicated to cheating clients through a Ponzi pyramid scheme.

Via a trust, ‘Fred’ and his colleagues offered to register aircraft as “N” (with less US controls), but the final destination of the money was a mining enterprise in Guatemala. Of the 190 transactions detected in his accounts, barely 10 corresponded to real sales – the rest were fraudulent manoeuvres, according to US prosecutors.

But in this case, a narco chapter should be added, according to those prosecutors, who alleged that several of the aeroplanes ended up crashing or confiscated in Central and South American countries with drug cargoes.

In 2021, wanted by the Texan courts, Machado fled first to Mexico and then to Argentina. He was arrested on April 16 at Neuquén Airport in Argentina's south on the orders of Interpol. Since then he has been under house arrest at his mother’s home in Viedma while his defence team – headed by Francisco Oneto, the lawyer of both Javier Milei and Espert – has sought to drag out his potential extradition.

Machado denies any links with drug-trafficking. In an interview with the WFAA channel in Dallas, he admitted to having diverted the funds of investors into a Ponzi scheme with aircraft but defined this as financial fraud with no drug connections.

“I’m not a saint, I’ve made mistakes, but I’m not a drug-trafficker,” he swore, promising to return the money if released. “The clients thought they were investing in one thing [aircraft] but were investing in something else,” the mine in Guatemala, he added.

When Machado was arrested in 2021, his relationship with Espert rose to the surface. The lawmaker played it down, accusing his rivals of mounting a political “operation.” The tensions coincided with the breakdown of his electoral partnership with his fellow economist turned aspiring politician Javier Milei, with Argentina’s two leading libertarian voices passing from allies to furious enemies.

Milei later told presenter and journalist Alejandro Fantino on his streaming channel that in 2021 he was offered US$300,000 to drop his campaign for national deputy. It was Daniel Parisini, better known by his alias ‘Gordo Dan,’ who gave the “bagman” a name and surname.

Milei “confirmed it to me personally. Espert had tried to make him drop his candidacy for money. That’s why he left Avanza Libertad and that’s how La Libertad Avanza was born,” Parisini wrote in a post on the X social network.

The spat distanced them for over two years until in 2023, following Milei’s presidential victory, Espert joined the libertarian front. A political reunion with pending issues which still echo.

Central crisis

When Milei was installed in the Casa Rosada as President in December 2023, Espert – or “el Profe,” as he was called – became a central figure of the libertarian government.

But when the media-friendly deputy was chosen as the top La Libertad Avanza candidate in Buenos Aires Province for this year’s midterms, the economist fell into the eye of the storm.

Cornered by the questions about his relationship with Machado, Espert had to talk. Initially, he acknowledged having made the businessman’s acquaintance in 2018 during the promotion of his book, La sociedad cómplice (“Society as Accomplice”), admitting that in 2019 he flew in his plane to Viedma. But he disassociated himself from the accusations, saying that he knew nothing of the illegal activities attributed years later to the businessman and defining himself as “naïve.”

According to his version of events, the aircraft and vehicles which he used were supplied by UNITE grouping under José Bonacci. “We candidates take what the party gives us. Do you ask if the taxi you take has had accidents beforehand?” he retorted.

Faced with the accountancy discovery linking him to a transfer of US$200,000, he dodged a direct reply, dismissing the document as “a scrap of paper” and accusing left-wing Frente Grande leader Juan Grabois, who filed a complaint with the courts on the issue, of mounting a smear campaign.

“I’m not going to give Grabois the satisfaction, I’m going to carry on,” Espert said defiantly. About his candidacy, he was categorical: “No way I’m going to resign. I’m stronger than ever. The President supports me.”

And Milei did. Yet the discomfort within La Libertad Avanza was evident after having made a banner out of the struggle against drug-trafficking and corruption with one of their leading figures now falling under suspicion. National Security Minister Patricia Bullrich was the toughest, demanding clear explanations from Espert, recalling that the party had raised the bar “the highest possible” and warning that narco links could not be tolerated: “José Luis has to go back to the media with clarity.”

The case also exposed the contradictions of the libertarian world. La Libertad Avanza national deputy Lilia Lemoine was one of Espert’s most vocal critics in the past, saying in 2019 he had been financed by a narco and accusing him of “treason.” Agustín Romo, currently an LLA legislator in the Buenos Aires Province legislature, had dubbed him a “bagman” for having boarded Machado’s aircraft.

Milei himself even signed a document in 2021 casting doubt on the origins of the funding of his ex-ally.

But October started with Espert as a ruling party candidate and, despite the noise triggered by his old connections, the government opted to shield him for the midterms.

Until the pressure became too much.

Awkward episodes

Beyond the Machado chapter, Espert’s political track record shows other awkward episodes. In May 2020, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, Carlos Maslatón organised a streaming show in which Gonzalo Díaz Córdoba, Espert’s former campaign manager, fired off grave accusations.

According to Díaz Córdoba, Buenos Aires City Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta had secretly financed Espert’s presidential campaign in 2019 in exchange for explicit support in the general elections. What is true is that after finishing out of the running, Espert caused surprise by requesting votes for Rodríguez Larreta in public, reviving suspicions of a covert pact.

In that same exchange, Díaz Córdoba vocalised his doubts about the management of campaign funds. Consulted as to whether “the campaign money had been embezzled,” he answered: “I don’t deny it ... I’ve no proof to the contrary.”

Espert “categorically” denied any contribution from Rodríguez Larreta but the controversy had already been installed. Maslatón admitted to having pumped cash “under the table” into the campaign but assured that he had felt betrayed on finding out that the Espert team had “fixed up with [ex-president Mauricio] Macri,” even suggesting that some collaborators were “rewarded” with City Hall posts after that agreement.

Such testimony paints a complex picture – while Espert was showing himself as an implacable outsider against “the caste,” his campaign had received money from businessmen linked to drug-trafficking and traditional political sectors. The contradictions are evident.

Espert, the same leader demanding “cárcel o bala” for the corrupt and narcos, appears linked to illegal contributions, the exchange of favours and inconvenient friendships.

The liberal deputy rejects all accusations, assuring himself to be the victim of media operations and – despite Espert’s decision to step down – Milei still backs him publicly. Machado’s shadow hangs over his figure and regardless of whether or not the courts advance or not, Espert’s credibility is in question.

Comments