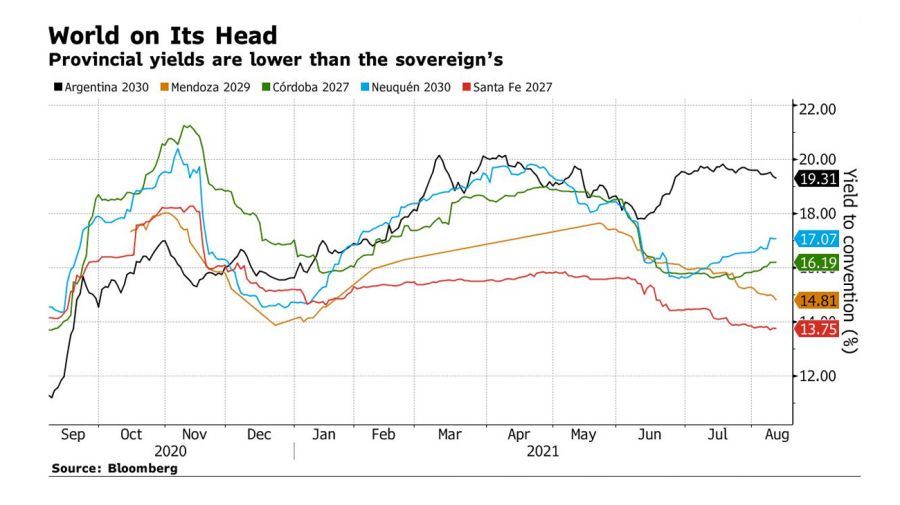

Nothing is seemingly ever normal about capital markets in Argentina, but things are getting even stranger. Over the past three months, overseas bonds issued by provinces have handily outperformed sovereign counterparts, cementing their status as the preferred choice for investors.

Provincial notes now yield about 2.8 percentage points less on average than Argentine debt with similar maturities. They’ve posted returns of almost 11 percent since the end of May, compared with near zero for sovereign debt, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

In most countries, of course, debt from the federal government is considered to be the safest investment around – in the United States, Treasuries are always going to yield less than municipal bonds, for example. But that isn’t the case in South America’s second-largest economy, where a history of defaults and economic mismanagement has scarred bondbuyers. Investors are also lured by the provincial notes’ higher coupons, as well as their history of providing much friendlier restructuring terms when things have gone belly-up.

“Sometimes good credits are in bad neighbourhoods,” said Siobhan Morden, the head of Latin America fixed income at Amherst Pierpont in New York. “The difference with Argentina is that the macro is tough, but almost every other credit pays you a coupon.”

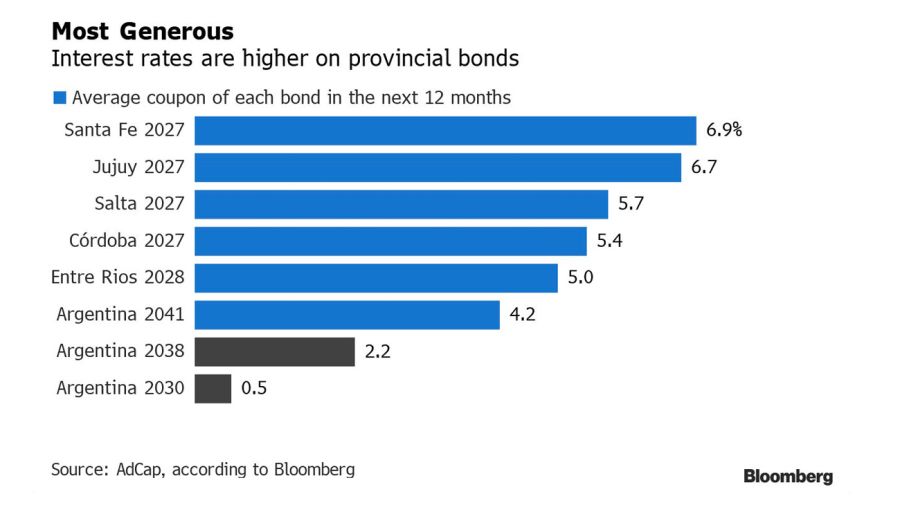

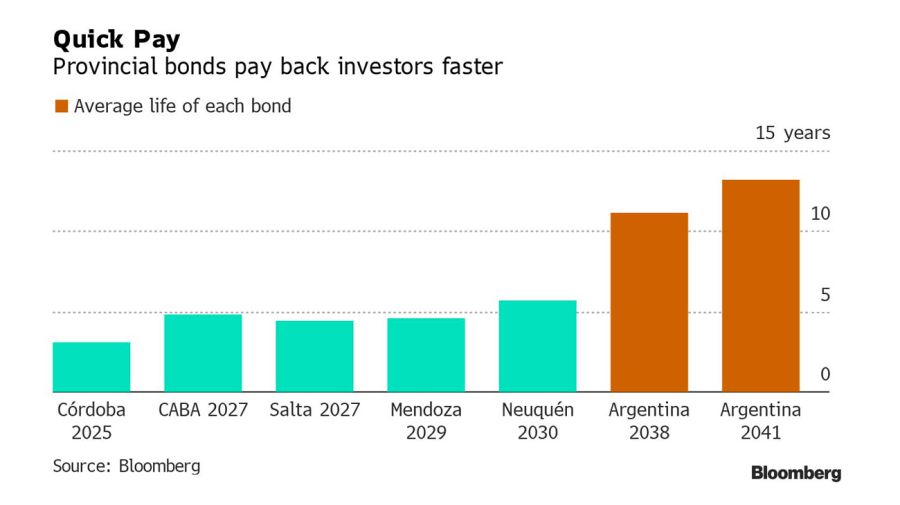

The dynamic has its roots in the federal government’s US$65-billion restructuring last year, which stuck investors with long-term debt with especially low coupons, a deal that gave bondholders about 37 cents on the dollar for their defaulted securities. By contrast, accords struck by provinces including Córdoba, Neuquén and Mendoza over the past few months gave investors back between 80 and 90 cents on the dollar in bonds with higher interest rates and shorter maturities.

There’s also some thinking that the provinces have more stable finances and might be a better credit risk, though that calculation is complicated. Local governments in Chaco, Córdoba and elsewhere posted primary fiscal surpluses last year, while the national government had a deficit of 6.5 percent of gross domestic product. But provinces are ultimately dependent on the Central Bank to sell them dollars to pay back investors, and it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which they’d get the cash they need if a cash-strapped federal government needs it even more.

While the provincial bonds are faring better than the federal government’s debt, almost all the notes are still deeply distressed. Neuquén’s bonds due in 2030, for example, yield about 16 percentage points more than comparable Treasuries.

Juan Manuel Pazos, the chief economist at TPCG Valores in Buenos Aires, points out that given the risks, provincial bonds have another advantage in their shorter average life – a measure of how long it will take for an investor to earn back their initial investment. Sovereign bonds due in 2038 or 2041 will pay about 15 percent of their principal before potentially destabilising presidential elections in October 2023. Provincial bonds due closer to 2030 will return about 20 percent of their face value by then.

The nation’s bonds may continue to underperform for the coming months, as the government increases spending to garner support ahead of the November midterm election. A deal between Argentina and the International Monetary Fund set to be agreed upon shortly after the restructuring last year, isn’t expected now until after the vote either. Investors are also watching commodity prices come off their highs, potentially weakening the country’s reserves during election season.

“Investors view provincial issues as better due to the sovereign’s history of default,” Ursula Cassinerio, a sub-sovereign analyst at Moody’s Investors Service in Buenos Aires, said in phone interview. “Most of the provinces have been doing well with debt lately.”

related news

by Ignacio Olivera Doll & Maria Elena Vizcaino, Bloomberg

Comments