President Javier Milei is experiencing the toughest weeks since taking office almost a year and a half ago, as a series of crises make a direct impact on his political capital.

The latest incident was the eruption of serious street violence in the vicinity of Congress midweek, where a march in support of retirees that was supposedly joined by organised groups of quasi-Mafioso football fans known as “barra bravas” morphed into something closer to urban warfare. There are serious questions as to what happened, even how much of it was potentially staged, but it clearly helped to distract the attention away from what was going on inside Congress and in the troubled port city of Bahía Blanca.

Inside the lower house, a fragmented opposition was looking to build a circumstantial majority to hit at some of the government’s major weak spots, including the crypto scandal regarding the ‘$LIBRA’ token, the attempt to circumvent the Senate by naming Supreme Court justices by emergency decree and the declaration of a public emergency for the natural disaster that battered Bahía Blanca. These three issues are extremely sensitive for Milei and his so-called “iron triangle" – composed of his Chief-of-Staff and sister, Karina Milei, and his lead political strategist, Santiago Caputo – who have all come under fire recently. While violence was raging in the streets, within the walls of Congress a pathetic exhibition of the worst of the tactics that both libertarians and the opposition utilise in their daily politicking occurred, including physical and verbal violence and even throwing cups of water at each other.

The situation in the streets was dantesque. A group of retirees have made a habit of marching on Congress every Wednesday to protest the evisceration of their monthly payments and purchasing power. In fact, some of them had been doing so since 2017, when Mauricio Macri passed a pension plan reform and the streets became a battleground. The 50 or so senior citizens that have generally marched on Congress since then received the backing of the “barra bravas” (which translates directly into the “tough” or “fiery crew”) hooligans, who are known for their violent ways. Anticipating this situation, Security Minister Patricia Bullrich said she would put in place strict security measures and challenged the hooligans to test her limits.

The cops were in position an hour before the official congregation time and the street battles started right on time, with the security forces taking a very aggressive stance. The alleged “barras” started throwing rocks, burning trash canisters and even torched a police car. Yet, there seemed to be no actual members of the organised hooligan groups associated with the myriad football clubs that populate the Buenos Aires metropolitan region, all of whom are well known both by their own members and specialised security forces. Perfil’s photography team, with ample experience in these types of situations, reported that there was no presence of a “shock force” or any union heavyweights. They also noted what appeared to be “infiltrated” violence-mongers amongst the protesters, while the police left a new patrol car unmanned, unlocked and turned on – an invitation to those hell bent on making trouble.

It was ultimately set on fire. There were also attempts at planting weapons which were captured by TV cameras. Gustavo Grabia, a specialised journalist who focuses on football hooliganism said that he checked with each of the groups mentioned by the Security Forces and that they confirmed they weren’t in attendance, noting that he only recognised two low-level and retirement-age “barras” at the march.

As the streets burned, tragedy hit when a freelance photojournalist was impacted directly by a tear-gas canister that was imprudently and dangerously shot straight at his head. He was quickly taken to an emergency room where at press time he remained in critical state, in intensive care. While there were obviously multiple violent actors participating in the march, the level of violence was clearly escalated by the security forces under the command of Bullrich and the suspicions of the violence being instigated and even coordinated by the government are elevated. A violent death as a consequence of police brutality could tilt the scales, pushing society from passive observer to direct participant, as has happened so many times in the recent past.

The Milei government is trying to pin the blame on Kirchnerism, “the left,” and the “barras” for causing violence. It is feeling the pressure of its unorthodox governing style. Choosing to embrace its legislative fragility, the President’s La Libertad Avanza coalition has relied heavily on DNU emergency decrees to get things done. Every President before Milei has used and abused DNUs, but the self proclaimed anarcho-capitalist has gone a step further, passing a major structural reforms package (the now famous DNU 70/23) and attempting to appoint Supreme Court justices Manuel García Mansilla and Ariel Lijo by decree. He’s also circumvented the legal obligation to inform Congress of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund — known as the “Guzmán law,” after former economy minister Martín Guzmán — via DNU decree. One of the most knowledgeable lawyers in the country recently said in a private conversation that this administration governs on the edge of constitutionality, noting that the level of abuse of the DNU stratagem could eventually backfire by spurring Congress or the Supreme Court into action. Indeed, Congress rejected a DNU for the first time ever under Milei, reinstating budgets for public universities while limiting earmarked funds for the SIDE spy agency, ultimately leading to a presidential veto.

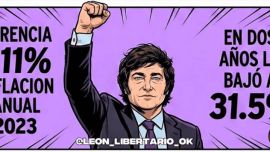

The libertarians have managed to govern with this level of institutional informality, given the fragmented state of the opposition and the personal popularity of the President, which is derived from his success at tackling inflation. Yet, multiple opinion polls show that this recent chain of events has affected his public image, particularly after the '$LIBRA crypto scandal. Milei hasn’t been able to shake off suspicions of corruption that include his sister Karina and several sketchy characters of his entourage. And that’s not to mention Kelsier Ventures’ Hayden Mark Davis, who has mysteriously disappeared from the public scene while lawyering up in the United States and Argentina. Davis hired Waymaker Law’s Brian Klein in the US and Marcos Salt in Argentina, while in the background he continues to move funds tied to $LIBRA in an apparent move to cash out, despite consistently saying that the funds are Argentina’s. Milei’s detractors have begun to call him a con artist (“estafador”).

Corruption has jumped as an important issue in the public’s perception, while Milei’s image has fallen. According to a recent poll by Atlas Intel, together with Bloomberg, the President’s positive image slid 10 percentage points in February to 45 percent, while negative perception grew nine percentage points to 50 percent. This has also fuelled a positive movement in Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s public image, even if she remains well behind Milei. Corruption is now the second major issue for those polled, growing from 33 percent to 41 percent, one percentage point behind high prices and inflation. The survey also included a political risk index composed of measurements of institutional instability, social conflict and crime and corruption. Argentina grew to the top spot among those surveyed (Mexico, Chile, Brazil and Colombia) surging 24 percent in a single month, the largest positive swing in the sample since at least October.

The catastrophe in Bahía Blanca also shows us that the national government is disoriented. A natural disaster of that magnitude, striking a port city toward the southern sector of Buenos Aires Province, should have been met with a coordinated effort by the Milei administration and its nemesis in the region, Governor Axel Kicillof. Instead, the national government did not manage to get the President to visit the town for five days, while Cabinet Chief Guillermo Francos indicated that reconstruction efforts were the responsibility of the district and the province. While desperate citizens were suffering the dawning realisation that they have lost everything, Milei and his sister were speculating as to whether it was beneficial to travel and show their support for fear of being insulted (they were). Though they finally made their way down and approved fresh funds for 200 billion pesos, it wasn’t a good look for the President and his sis.

Milei remains well ahead of his opponents in voting intention measurements ahead of this year’s midterms. Society has tolerated his eccentricities and distaste for the institutions of democracy thus far. He may begin to pay a price, so he better hope for those IMF funds in order to keep the economy going.

Comments