Just three years after Argentina’s local markets were brought back from the dead, they’re barely clinging to life.

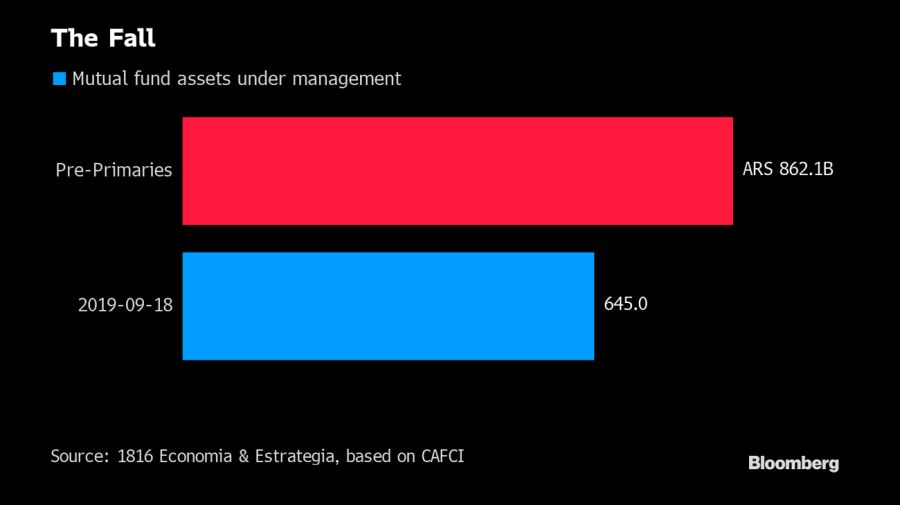

Assets under management at local banks and brokerages have plummeted 25 percent since the August PASO primary vote signalled pro-business President Mauricio Macri has little chance of winning re-election this month. Stock trading has fallen by half, and local bond volume is down by two-thirds.

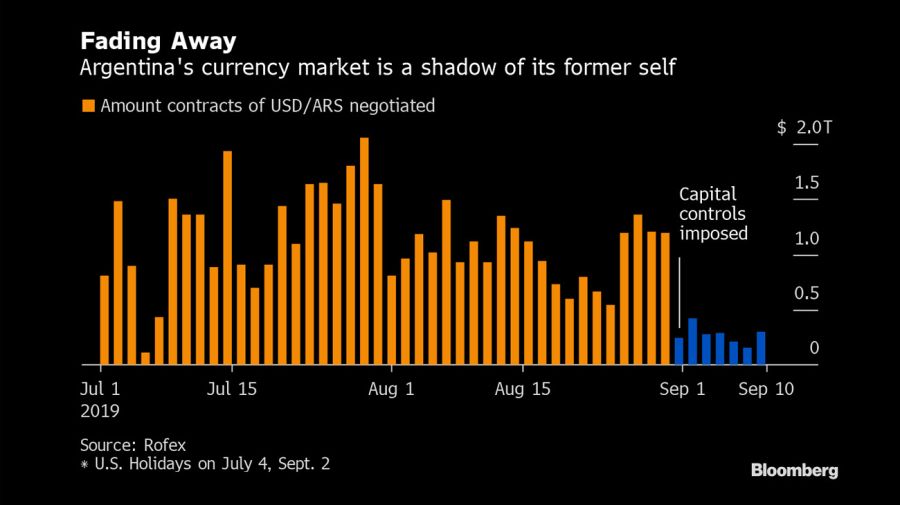

On top of that, Argentines sent a record amount of dollars overseas in August as the government delayed debt payments, said it would try to impose a restructuring on foreign notes and re-imposed capital controls to try to save the peso. For a few days, emergency measures prevented many investors from taking money out of mutual funds.

It’s all been a disaster for the investment banks, consultants and brokerages that opened Buenos Aires offices or rushed to expand expecting a groundswell of activity after Macri took office in late 2015. Now all those bets have been upended. Within hours after the opposition ticket led by Alberto Fernández won the primary election by more than 15 percentage points, markets started tumbling amid concern his leftist policies would derail economic growth.

“There’s a great uncertainty, and that’s making the decision-making process quite difficult,” Pablo de Gregorio, a partner at Ernst & Young, said at an event last week where he was presenting a survey of business executives held after the primaries. “And we all know the impact on our companies when decisions are delayed.”

The early days of Macri’s administration were filled with promise. Putting an end to 12 years of populist rule, he issued more than US$40 billion in overseas debt, including a 100-year bond, and hired a dream team of financiers for his Cabinet.

Assets under management at mutual funds skyrocketed to a record, and firms including BTG Pactual, Julius Baer, Moneda Asset Management, Credicorp and LarrainVial obtained local licenses to operate in the financial markets, opened offices or hired and moved employees to the Argentine capital.

But Macri never managed to rein in inflation and by early 2018, with the peso sinking and interest rates soaring, his government sought a record US$56-billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). All that cash came with the requirement the government take politically unpopular measures to pare its spending.

And as Macri struggled to turn the country around, there were signs some investment shops were retreating even before the primary. Morgan Stanley relocated its head of Latin American equity capital markets, Manuel García Díez, to Argentina from New York in 2017 as the initial public offering pipeline swelled to US$3.5 billion. As corporate growth plans withered, the IPO pipeline fizzled and Díez left the bank earlier this year.

The Swiss private banking firm Julius Baer had sought to partner with a local broker and held advanced talks to buy a 20-percent stake in Max Valores in 2017, according to a person familiar with the matter. The idea was abandoned in mid-2018 as Argentina headed toward the IMF bailout. The bank’s press office declined to comment.

Now, just US$15 million a day is being traded on the local stock market, down from an average US$30 million in 2016 and 2017. Hopes of a huge inflow of capital and a wave of initial public offerings triggered by MSCI Inc.’s decision in June 2018 to upgrade Argentina to an emerging-market classification, from frontier market, have been all but dashed.

Bond trading has fallen to US$300 million a day from more than US$1 billion before the primary elections. The illegal so-called foreign-exchange “caves” where Argentines seeking to skirt capital controls buy dollars, however, are once again booming. Their business had slowed over the last couple of years as controls were removed, but retail demand is back.

It’s quite a turnaround from June 2016, when Macri told a room full of finance executives meeting at the stock market that “we need to once again have capital markets up to international standards.” The market value of Argentine stocks is now US$27.6 billion, half the level it was when Macri took office.

“A lot of small brokers that opened in recent years will disappear,” said Alejo Costa, the chief Argentina strategist at BTG Pactual in Buenos Aires. “It’s tough to keep a structure running if there’s no market volume. The market will have to consolidate, and shrink in real terms and in dollar terms.”

Argentina and its financial markets appear to have somewhat stabilised after the fallout from the election. Partly due to the capital controls, the official exchange rate has held steady for a few weeks along with bond yields.

But that’s not to say there’s much optimism before what’s likely to be Fernandez’s takeover of the government on Dec. 10. Credit-default swaps show investors pricing in a 55-percent chance of Argentina missing a payment on its overseas bonds within the next year and a 94-percent chance within five years.

Local money managers are left wondering if it will ever be possible to recover the confidence of investors, both domestic and foreign.

“We need to be able to foresee the rules of the game– it’s the same in mass consumption as in soccer,” said Guillermo Rimoldi, the chief executive officier of candy-manufacturer and agribusiness firm Georgalos. “It’s unfeasible to play the game and know where to kick the ball when the goalpost is constantly moved.”

related news

by Ignacio Olivera Doll & Carolina Millan, Bloomberg

Comments