Twenty years ago, Argentina experienced its worst economic and political crisis.

The scars of the biggest debt default in global history, the collapse of convertibility and the confiscation of bank deposits amidst a popular uprising remain fresh in the memory for many. Today, a generalised mistrust of the nation’s politicians remains. The roots and sentiment behind the shouts of “Que se vayan todos!” remains. The pain caused by the deaths of some 40 people, killed by police bullets during demonstrations and looting, remains.

The fall of Fernando de la Rúa's government came in the midst of a power vacuum following the collapse of the one-dollar-to-one-peso exchange rate anchor, a model which, together with privatisations and uncontrolled trade liberalisation, had given a false illusion of prosperity to an impoverished country.

Thousands of people rushed into supermarkets to loot food, a brutal contrast to the time when many Argentines bought luxury imported goods thanks to an overvalued peso.

The trauma of 2001 has entered the collective memory. "There was a strong sense of orphanhood, distrust of institutions, the state and the banks," historian Felipe Pigna told the AFP news agency in an interview.

Savers screamed and shouted for the return of their money blocked in the banks in the 'corralito,' the sweeping restrictions on banking implemented by Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo in an attempt to prevent the collapse of the entire system.

"Chorros, chorros, devuelvan los ahorros! [“Thieves, thieves, give back the savings!"] the people chanted loudly as they hammered on the lowered shutters of banks across the country.

Cavallo had been a minister under the right-wing Peronist former president Carlos Menem (1989-1999). He was the father of the Convertibility plan, which lasted 10 years until it exploded under De la Rúa.

"Of the 77,000 dollars I had in the bank, I lost 40,000 in the 'corralito.’ That December was terrible, there were riots everywhere," computer scientist Ricardo Lladós, 71, recalled in an interview.

Recently, famous actor Ricardo Darin recalled tearfully how his late mother "right up until her last days, asked me if there would be a chance of recovering the money she lost at the bank."

Eventually, he decided to lie, telling her "it's in the hands of lawyers, and they say it should be possible. You should have seen the way her eyes lit up."

A country on fire

"There is a bittersweet taste of 2001: on the one hand the total tragedy and on the other the healthy reaction of the people on their own, trying to rebuild a situation of disaster, of catastrophe," Pigna said.

"I remember with great sadness seeing my workshop at a standstill," Fernando Soto, 57, who was the head of a metalworking shop at the time, told AFP.

A pioneering cardiology study found that in the period from April 1999 to December 2002, there were 20,000 more fatal cardiac arrests in Argentina than would normally have been expected, partly due to stress but also because of the degradation of the health system.

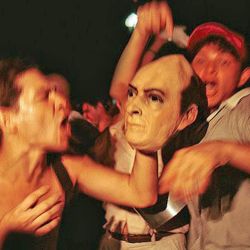

In the midst of the chaos, De la Rúa decreed a state of siege on December 19. The police charged on horseback against the Madres de Plaza de Mayo. It was like adding fuel to the fire. Hundreds of thousands more took to the streets.

"The memory is of blood, pain and the state of siege that is a thing of a dictatorship," Pigna reflected.

De la Rúa, from the conservative wing of the social-democratic Radical Civic Union (UCR), resigned and escaped by helicopter from the Casa Rosada, while it was surrounded by demonstrators, at dusk on December 20.

"He abandoned ship in an unprecedented crisis, with an enormous social cost, a geometric increase in poverty [to 57 percent] and unemployment [20 percent] and millions of people affected by the [subsequent] devaluation of the peso," Pablo Tigani, an academic with a master's degree in international economic policy, explained in an interview.

The public debt was unpayable. Appointed president by Congress, the Peronist Adolfo Rodríguez Saá declared the largest default in history for US$100 billion (70 percent of the country’s debt liabilities). He lasted a week in power.

Another right-wing Peronist president, Eduardo Duhalde, took office and called for early elections. This led to the emergence of another Peronist president, Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007), who began the Kirchnerite era that continued with two terms in office for his wife, current Vice-President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

During this period Argentina cancelled its debt with the IMF in a payment of US$9.5 billion and restructured bonds with the support of 93 percent of creditors. The rest was settled in lawsuits with the so-called "vulture funds," which bought the defaulted debt and litigated in the United States for payments and profits.

Chronic debt and inflation

Argentina, in the midst of a new currency crisis, again sought help from the IMF during the mandate of the conservative leader Mauricio Macri (2015-2019). It received the largest credit-line the agency has ever granted to a country: US$57 billion, of which US$44 billion was disbursed.

Macri argued that the funds were used for payments to private banks that were considering leaving the country, so that they could recover investments.

Argentina faces maturities of about US19 billion per year in 2022 and 2023, and its meagre international reserves and economic situation – the country has been in recession since 2018, with inflation at 51 percent annually and poverty at 40.6

percent – force it to renegotiate with the Fund once again.

Although banks now have to back dollar deposits (20 percent of the total), there are still exchange controls. The scars still run deep: fake news of a new 'corralito provoked a flurry of withdrawals in November.

"2001 is a ghost that reappears in times of crisis. Not in rational terms, but in emotional terms," concluded Piña.

Chronology of Argentina’s 2001 collapse

Tracking the key moments in the institutional, social and economic crisis that gripped Argentina and put an end to President Fernando de la Rúa’s government, and to convertibility.

1999

December 10 – The centre-left Alianza coalition takes office led by President Fernando De la Rúa, from the social-democratic Radical Civic Union (UCR), and Vice-President Carlos Álvarez, of centre-leftists FREPASO. They promise to retain the Convertibility plan, which pegs the peso to the US dollar on a one-to-one exchange rate and has been in place since 1991.

2000

October 6 – Vice-President Alvarez resigns in disgust over allegations of government bribes to legislators to vote for a labour reform. In two months, banks lose US$1.8 billion in deposits.

2001

January 13 – Financial protection is agreed with the IMF, with Argentina offered almost US$39 billion to pay down debt maturities. In exchange, a strong fiscal adjustment and reform of the pension system is demanded.

March 11 – The flight of dollar deposits from banks accelerates.

March 20 – Domingo Cavallo, architect of the Convertibility plan with former Peronist president Carlos Menem (1989-1999), is re-appointed economy minister.

June 19 – A massive sovereign debt restructuring, known as a 'megacanje', is agreed. Rates of return of up to 16 percent are agreed.

July 30 – The Zero Deficit Law (Ley de Déficit Cero) is passed, delivering drastic cuts in public spending. State salaries and pensions are cut by 13 percent.

October 14 – Alianza is defeated by Peronist forces in midterm legislative elections.

December 1 – Cavallo announces the 'corralito,' freezing bank accounts and blocking withdrawals from US dollar-denominated accounts. Only 250 pesos a week (the equivalent to US$250) is allowed to be withdrawn. Protests break out in front of banks and chaos erupts.

December 5 – Sales in shops collapse by 50 to 70 percent. Informal barter clubs are formed nationwide, reaching more than 1.5 million people. The IMF concludes that the government’s economic programme is "neither sustainable nor viable" and refuses to release a disbursement of US$1.26 billion. Country risk hits close to 4,000 points.

December 6 – The government issues 'quasi-currencies' in order to pay salaries.

December 7 – Cavallo travels to Washington. He declares he will stay there until the IMF releases the funds.

December 8 – Tense queues form outside banks, which open on a Saturday for the first time in history.

December 9 – Cavallo agrees to cut a further US$4 billion from the budget in order to receive IMF aid.

December 12 – ‘Cacerolazo’ pot-banging protests take place in Buenos Aires and across the country.

December 13 – Strike called by main labour federations.

December 18 – Looting begins, with food in supermarkets targeted.

December 19 – By now, children and entire families are involved in the looting. Police repression is unleashed with deaths and injuries reported. De la Rúa declares a state of siege. ‘Cacerolazo’ pot-banging protests continue as citizens march on the Casa Rosada.

December 20 – Cavallo and his entire Cabinet resign in the early hours of the morning. Hours later, tear gas and bullets are fired at the demonstrators. Heavy clashes break out. Five people are killed in the centre of Buenos Aires. The death toll rises to 40. De la Rúa resigns and escapes the Casa Rosada by helicopter.

December 21 – Congress elects the head of the Senate, Peronist Ramón Puerta, as provisional president. Adolfo Rodríguez Saá takes office as president elected by Congress.

December 23 – Rodríguez Saá is sworn in and declares an immediate default on US$100 billion – the largest in world history.

December 30 – Rodriguez Saá resigns due to lack of political support. The provisional president, deputy Eduardo Camaño, calls an emergency meeting of the Legislative Assembly.

2002

January 1 – The Legislative Assembly elects Senator Eduardo Duhalde, who had lost the elections to De la Rúa in 1999, to serve as president until 2003. "Those who deposited dollars will receive dollars," he vows on taking office.

January 6 – Duhalde repeals the Convertibility Law. The peso depreciates by 30 percent. Duhalde's promise was never kept.

– TIMES/AFP

Comments