After conquering the immensity of the country and helping to build a nation, Argentina’s railway network fell into disgrace for a long time. Now, trains are making a comeback, station by station, although there are doubts whether this incipient return has a viable future.

Far from the River Plate, the rising sun is blinding. The diesel-electric CNR CKD8 locomotive chugs out of the countryside bit by bit, slowly advancing towards Buenos Aires. Still sleepy after hours of travelling, the passengers nevertheless express their joy that "trains are back."

From San Pedro, 170 kilometres north of the capital, most are travelling to Buenos Aires for business reasons, for a medical check-up or to see family. The passengers do not move fast (the journey takes 200 minutes) but it’s a cheap trip (1,130 pesos or US$5.10 at the day’s official exchange rate) and they will be back home that same night.

"Beforehand, there were trains but they departed every now and then. This one leaves every day and has changed my life quite a bit," smiles 52-year-old Noemí Peralta, who is travelling 280 kilometres to buy garments wholesale for sale in her city of Rosario.

"Going by bus at 5,000 pesos (US$22.60), my profit margin would be absorbed or I’d have to sell the stuff dearer. Now I go happy because I can bring back a ton of things," she says.

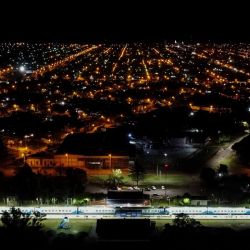

Justo Daract, Gobernador Castro, La Picada... after the recovery of the concessions from private hands a decade ago, President Alberto Fernández’s government has been re-inaugurating stations, some of them very small, and restoring branch lines that were abandoned 20 years ago or more.

Born together

"We have reconnected 66 localities with our freight and passenger trains, taking over 2,500 kilometres of rail and reactivating 17 branch lines," said the president in a speech back in March.

The preceding government under then-president Mauricio Macri had closed down 12 branch lines, as emphasised by the Transport minister at that time.

Railways have a distinguished place in history and in Argentine hearts. They were practically born together.

"Unlike Europe, there was virtually nothing in the Americas before the railway. It was a state instrument to develop and create a country which did not exist," explains Jorge Waddell, a professor of public policy and an Argentine railway historian.

Bearing testimony to that rich past are the railway museum of Buenos Aires and the majestic stations of Constitución (1887) and Retiro (1915), where fine arts and Victorian influences mingle since it was the British who started off the railways.

Those were times in which Argentina was projected as the "granary of the world" for its production of meat and wheat, multiplying railway lines to the degree of absurdity to form a network with tracks running parallel a few kilometres away from each other.

But of the 45,000 kilometres of track that existed in 1945, its historic peak, today only some 15,000 kilometres remain, of which 5,000 kilometres are for passenger transport only in a country five times the size of France, which has 27,000 kilometres of track.

A social role?

Nationalised in 1948 under the first government of Juan Domingo Perón (1946-1955), Argentina’s extensive railway network suffered from a lack of investment until it was in large measure dismantled in the 1990s during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989-99).

"The railway system was an invalid connected to an iron lung for many years, until the plug was pulled out," explains Waddell regarding the policies of the 1990s.

However, Waddell has little trust in the current viability of the railways: "An impoverished society cannot pay the fares so practically 95 percent are subsidised by a bankrupt state, while the passengers pay five percent of the cost," he explains.

Trenes Argentinos, the public company which resumed management of the network in 2014 (although there are private concessions for freight trains), recognises that the numbers do not balance out. Nevertheless, it considers recovery of the system to be a "state policy."

"We think of management in terms of social, not economic profitability," says Mariano Marinucci, the president of Trenes Argentinos.

"The train represents a social right for citizens and a service for communities," he underlines.

In the blue-and-white Trenes Argentinos train linking San Pedro to Buenos Aires, the passengers enjoy spacious, air-conditioned carriages (which were brought from China in 2014), a restaurant-car and free hot water in each carriage for consumption of the traditional and indispensable mate infusion.

Pensioner Eduardo Llama, 68, who "returned to the train" three or four years ago, rejoices but he laments that the tracks "are slower than they were 50 years ago," due among other causes to the antiquated state of some tracks and level crossings.

Yet people keep loving the train, cheap and safe, because it evokes memories of infancy and family life.

According to Waddell, "failed states like Argentina yearn for times gone by because the only positive point of reference they have lies in the past and the train is essential to our past."

related news

by Philippe Bernes-Lasserre, AFP

Comments