A chapter of Televisión por la identidad is running and while he watches, the 27-year-old cannot stop the questions bouncing around in his head. He recognises much of what is happening to the protagonist – the circumstances of his birth, the profession of his presumed father and the militaristic outlook he tried to drill into him. He also shares the character’s essential doubt: “Could I be one of the grandchildren?”

For Guillermo Amarilla Molfino, that question was not going to have an immediate reply, but it would finally arrive thanks to the struggle of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and the existence of the National Bank of Genetic Data (BNDG, in its Spanish acronym).

In the closing months of 2007, Guillermo (then known as Martín) came to grips with his fears. Around the time he saw the television programme, he approached CONADI, the Comisión Nacional por el Derecho a la Identidad.

With its help, he gathered evidence: apart from having been born in Campo de Mayo Hospital in 1980, he learned his birth certificate was signed by the military doctor Julio César Caserotto, a man linked to the handover of babies born in captivity.

Everything pointed to his doubts being well-founded. But in order to confirm whether or not he was the son of missing people from the last military dictatorship, one decisive step lay ahead: genetic testing.

‘People of interest’

Almost 1,200 people approach the BNDG annually, sent by CONADI or at court request. A blood sample is extracted from them and their DNA is analysed to see if it matches any of the families in the institution’s database. The current waiting list is 278, nursing the hope of finding their grandchildren illegally snatched away by state terrorism.

Guillermo went to Durand Hospital where the laboratory then functioned (since 2015, it has had its own premises in Córdoba Avenue) with the certainty that the result would be positive. Four months later, on March 6, 2008, he was notified that his genetic profile did not match any of the families in the Bank.

“For me it meant lowering the blinds and closing the door because the first thing I thought was: ‘How could I suspect?’ Guilt kicked in,” he recalls today.

He carried on with his life but his DNA also took a path of its own, passing to form part of the samples of “people of interest” who doubted their identity (currently a total of 12,000), conserved in the Bank to be compared again every time a new family group is added to the database.

‘Burning question’

The BNDG is a model institution, the first of its kind in the world, created 35 years ago this month.

“Forensic genetics as used today was developed due to the burning question of the Grandmothers [of Plaza de Mayo] over how to bring up the children in the absence of their parents,” highlights BNDG lab chief Nicolás Furman.

Before 1987, work had already begun on obtaining samples, even succeeding in restoring Paula Eva Logares to her family in 1984 – the first granddaughter genetically matched to her grandmother.

“But then we began to realise that a grandchild not matching any family might match another group appearing subsequently. That’s why the Bank was constructed with the idea that when the samples arrive, they are not matched case by case but against the entire database,” explains Furman.

Reconstruction

Marcela Molfino and Guillermo Amarilla were kidnapped in different places on Peronist Loyalty Day, October 17, 1979. It is thought they were first held at the ESMA Navy Mechanics School and then transferred to Campo de Mayo.

Her family did not know that Marcela was pregnant, so they only denounced the kidnapping and disappearance of the couple. Their genetic patterns were not sent to the BNDG.

In 2009, a survivor testifying at one of the Campo de Mayo trials informed that a woman had given birth at that clandestine centre on a date close to the birth of Guillermo. Thanks to their research work and the cross-checking of data, CONADI communicated with the Amarilla and Molfino families requesting DNA samples.

“All the family members available were summoned: grandparents, uncles and aunts, siblings and cousins. With today’s technology, the more people, the better. If all four grandparents are still around, the genetic answer will be found for sure,” explains Furman. “Each time a person is entered, irrespective of the charges made, they are compared with all the family groups seeking loved ones, and the reverse.”

The incorporation of the DNA samples of both families permitted fresh cross-checking with those already registered.

Emotion

Towards the end of October, 2009, the results confirmed that Martín Gonzalo Jorge García de la Paz was the son of Guillermo and Marcela. That November 3, the identity of grandchild N° 98 was restored.

“CONADI called me up on a Friday and told me that I had to go there the next Monday. When I got there, I was attended by Claudia Carlotto, the daughter of Estela [Barnes de Carlotto],” said Guillermo. “Then Claudia began to tell me the story of a family. I did not twig until she cut to the chase: ‘It’s your family, do you want to know them?’”

Initially, he didn’t understand much of what was going on. Guillermo didn’t expect it. “Then we embraced and she told me that I had three brothers who lived in Chaco and had come to see me.”

Guillermo still remembers the joy later that day at the offices of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. The emotion was great – not only were all three of his brothers there, but also uncles, aunts and cousins.

“They were a crowd. They had filled up two buses to come,” he sums up, laughing. They were crying out “with relief and joy,” he recalls.

The first thing he asked for was a photo of Marcela, his mother. “One of the first things I wanted when I reached the Grandmothers was to see an image of her. I looked at her thinking: ‘She’s my mum.’ And that was that, ever since that day.”

That gesture, that image and the feeling of having lifted a great burden brought him calm, he explains. “That’s the difference between a life of lies and a life of truth,” he sums up.

Certainty

Furman says the key to all this lies in the reliability and certainty of the lab’s results.

“When a comparison results positive, the first thing to be done is to analyse everything again – i.e. typify the genetic markers again and repeat the comparisons and the studies of the DNA and the mitochondria, everything,” explains the BNDG lab chief.

Only then is there communication with CONADI or court prosecutors and the Grandmothers.

“Those calls are pure celebration,” Furman smiles, adding that in the four years he has been doing this job he has had “the good luck” to participate in three recoveries of identity.

Guillermo Amarilla Molfino decided to leave behind not only his surname and the history of his illegal adopters but also his former given names. He chose to take his father’s instead: “At first I stuck to my first name but decided to cancel it within two or three years of learning the truth because it no longer represented me.”

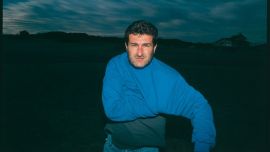

Now aged 41 with a daughter of six, he works in the Museo del Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos (ex-ESMA) museum and is part of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo organisation.

“I had the good fortune of my case being resolved before my daughter’s birth, so that she does not have to live the damage from baby-snatching. We know that this damage has generational transfer, multiplying and apparently endless. She was born and will grow up with truth and love,” he reflects with a smile.

related news

by Evangelina Bucari, Télam

Comments