An outsider candidate for Argentina’s presidency is gaining traction by tapping into voter anger at rampant inflation.

With no sign of relief in sight, Javier Milei, an economist-turned-congressman best known for his combative television appearances, senses an opening for his brand of rage-filled rhetoric. A Donald Trump acolyte with a reputation for political theatrics over policy specifics, pollsters say his challenge needs to be taken seriously going into October’s elections.

One reason is that Argentina’s deeply polarised political class is in crisis, with the ruling Peronist coalition and the main opposition each in disarray and still unable to identify a respective presidential candidate. But Milei’s real bonus is that neither of the established blocs, populist or pro-market, has been able to fix an economy lurching deeper into the abyss.

“Obviously, as inflation goes up, more people intend to vote for me,” Milei, 52, said in an interview in Buenos Aires in February.

Milei’s blow-up-the-system message is calibrated to resonate in times like these, and the relentless stream of bad economic news is running in his favour. Data released Tuesday showed annual inflation surpassed 100 percent for the first time since the early 1990s, bringing back memories of the hyperinflation that ravaged South America’s second-largest economy.

With nearly 40 percent of the population mired in poverty, Milei casts himself as a saviour in a “moral revolution.” His responses to the malaise are correspondingly dramatic, and include swapping the Argentine peso for the US dollar as a national currency and slashing government spending. He’s even suggested burning down the Central Bank.

It’s all part of his aggressive style of politics, which he says crystallised when he attracted blanket criticism for his conservative views: “I realised the only way is to fight.”

It’s an approach that appears to be winning over Argentines.

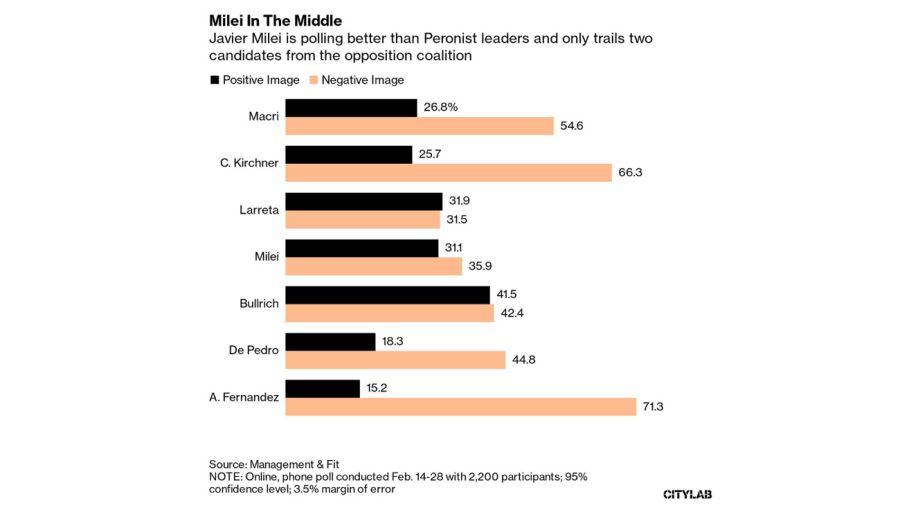

More than 31 percent of voters have a positive image of Milei, who scores higher than President Alberto Fernández or any other potential Peronist candidate, a February poll by consulting firm Management & Fit in Buenos Aires found. Milei’s positive rating is in a dead heat with one opposition candidate, Buenos Aires City Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, and trails only former minister Patricia Bullrich.

Although polls were notoriously off in the 2019 presidential race, nobody doubts that Milei is taking votes from both coalitions whose respective bases have until now been untouched.

Milei “reflects the failure of Argentina’s political class,” said Julio Bárbaro, a former Peronist congressman. “He expresses voters’ anger.”

Milei is aware that economic turbulence is his runway for take-off. Argentina has spent more time in recession than any other nation since World War II with the sole exception of the Democratic Republic of Congo, World Bank data shows. Another is looming this year, as a historic drought destroys crop harvests that are essential to bring in US dollars for government coffers and to fuel growth.

Mónica Troncoso, 46, remembers past looting and anarchy during hyperinflation and says Argentina is close to a return to those days. Living in poverty, working multiple jobs and in receipt of welfare payments, Troncoso sees a “social explosion” unless Argentina takes a turn for the better soon.

And she worries that could create the conditions for a Milei upset. She’s already witnessed his electoral potential, living in the poor Barrio Fátima area of Buenos Aires where he recorded his best performance in the 2021 midterms, a result that helped catapult him into Congress.

“I’m afraid there could be some type of breaking point and that people accept Milei as their leader,” said Troncoso, who described her politics as “very left” but said she’s still to decide whom to back this year. “The one who creates more chaos will reign.”

Milei sees his voter base as strongest in Argentina’s largely poor northern provinces rather than merely the wealthy farm belt and the capital. And he’s gaining ground in areas where the Peronists, the dominant political force of the past 70 years, have long held sway.

His election strategy isn’t complicated: Make it to the second round and light the fuse. “If we get to a run-off, we’ll win,” he said. “It doesn’t matter who our rival is.”

Born and raised in the city of Buenos Aires, Milei climbed the corporate ladder, serving as senior economist in Argentina for HSBC and other firms before becoming an adviser at Corporación America, the holding firm run by billionaire Eduardo Eurnekian, and appearing at Davos.

At first he penned mild-mannered analysis and opinion columns, then he was invited on TV as a conservative pundit. After the 2019 election that returned a divisive Peronist coalition, he started appearing more frequently on talk shows, where his furious exchanges with left-wing pundits went viral. His talks soon went from hushed hotels to rockstar-style rallies.

Despite his growing fan base, Milei faces mounting resistance for overstepping the mark. As president, he’d eliminate the newly created Women, Gender & Diversity Ministry and the government-run INADI institution advocating against racism. He said he’d move to eliminate Argentina’s abortion laws because he considers the act murder. His poll numbers dipped last year after he expressed support for the sale of human organs and loosening regulations on gun purchases in a country largely devoid of household firearms.

Milei has few political allies, describing politicians as delinquents, thieves and criminals for mismanaging the economy. He considers the government printing money to finance spending a crime — it’s not — and casts a narrative of political leaders enamoured with high inflation. To dollarise the economy, he suggests pushing through a type of referendum that doesn’t require congressional approval, and said he’d prosecute any lawmaker who didn’t abide by the result.

Without having announced all the candidates on his ticket for governor, Senate or house, questions remain over how much national reach he will have. Martín Tetaz, congressman for the main opposition coalition, Juntos por el Cambio, still sees a clear chance for Milei to place first in the August primary vote if neither main bloc fields a single candidate, and to progress from there.

“Milei is going to get more votes than everybody thinks,” Tetaz said.

Single with no children and never married, Milei has five dogs, four named after economists. He says his image — sideburns, dishevelled hair, frowning in photos — is natural. If so, it’s meticulously crafted. His make-up artist carefully whisks his hair into dramatic form. He gives instructions on how to photograph him. Milei insists he can’t go on a dinner date partly because “120 people would come and ask me for selfies.”

Cinthia Fernández, a single mother from the low-income district of La Matanza south of the capital, asked for one such selfie. She hugged Milei at his campaign headquarters in February as he raffled off his congressional salary, a monthly publicity stunt. His tough-on-crime and corruption message resonated with Fernández, whose hometown is known for its poverty.

“My president,” she said as the two embraced.

Whether he takes the top job or not, Milei’s support shows that as much of Latin America from Colombia to Brazil has shifted left, Argentina is tacking right. Even the Fernández government, facing approval ratings in the teens, is starting to implement Washington consensus policies, such as budget cuts and high interest rates to comply with a US$44-billion programme with the International Monetary Fund.

For ordinary voters, Fernández’s shift from populism to austerity hasn’t delivered economic results. Nor did his business-friendly predecessor, Mauricio Macri, whose opposition party may run multiple candidates this year. Vice-President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who governed for two-terms before Macri, also left a trail of economic distress.

Milei’s greatest appeal may be that he’s not a part of that political class.

Juan Germano, director of polling firm Isonomía in Buenos Aires, said Milei stands to win political power and seats in Congress even if he doesn’t take the presidency. And that could impact all of Argentina.

A Milei with five percent of the vote “isn’t a big deal,” while 10 percent support “is a problem for the opposition coalition,” said Germano. “A Milei with 15 percent of votes is a problem for everybody.”

related news

by Patrick Gillespie & Ignacio Olivera Doll, Bloomberg

Comments