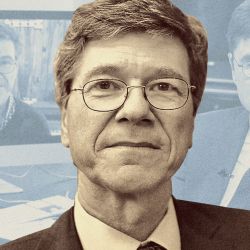

Economist, professor and public policy analyst Jeffrey Sachs is considered one of the world's leading experts on economic development and the battle against poverty.

A best-selling author and leading educator, Sachs spoke to Perfil’s Jorge Fontevecchia this week for an exclusive interview, which will be broadcast this weekend on NET TV. Here, in print for the first time, are extracts from their extensive conversation.

It has been reported that two months ago, you told Alberto Fernández not to get into trouble because of a default lasting a few months, because there would be several countries also asking to renegotiate their external debt. Would you make the same recommendation today?

I think that Argentina is doing the right thing, which is to make clear that the debts need to be restructured. It's doing it seriously, based on rigorous data.

Its position is supported by the International Monetary Fund technical staff, which is quite important and useful. It's rather straightforward to calculate the debts that carry the high-interest rates that Argentina carries right now are not compatible with the basic stability and well-being of the people of Argentina and therefore need to be restructured. Some countries are able to refinance their debts by borrowing at very, very low-interest rates today and repaying their old debts. Companies are refinancing their debts, governments are refinancing their debts – it makes perfect sense for Argentina, which has coupon rates of seven percent on many of the bonds, to restructure these debts to interest rates of two or three percent, which is what the world market rate is right now – even lower for some countries. So I think that the government is doing the right thing.

We're in a very deep global crisis. Argentina's in a very significant crisis. Like all parts of the world, in terms of Covid and the economic impacts of the epidemic. And so I don't really see a more reasonable way forward than what the government is doing.

Argentina made an offer to restructure its external debt, one that was not approved by creditors. Could Argentina be being used as a laboratory by creditors in the face of future sovereign debt restructurings after the coronavirus?

Certainly, creditors are aware that they don't want to make precedents for other countries or invitations to other countries to reschedule. So I would not have chosen Argentina's timing, if there were a choice. [But] It wasn't a choice for the government. It was a reality, unfortunately.

The fact of the matter is, creditors are aware that when they make a deal with Argentina that becomes a foundation for deals that other countries are going to require. And so in this way, they hold out. They appeal for themselves to be bailed out by the IMF or by others. And there is a time delay in this. But I don't find that either surprising or really very worrying or anything that one can do about this.

The key, in my opinion, is for Argentina to behave in good faith, to be clear, transparent. To be in close cooperation with the IMF, which it is right now in estimating fiscal space, in identifying the range of restructuring that's needed. What more can a debtor country, with a government that inherited an overhang of unsustainable debt, in the middle of this unprecedented epidemic do? The fact that creditors are some in some cases recalcitrant – others have agreed already – but in some cases they are recalcitrant... this is par for the course. Things don't come immediately.

It's not ideal. I'd rather see an agreement reached early on. I think it would be mutually beneficial. And maybe if it were just Argentina and the creditors by themselves, you'd get a faster agreement.

Bondholders argue that a moderate write-off would be better for Argentina, in order to return to the voluntary debt market. Argentina's economy minister, Martín Guzmán, maintains that he prefers a reduction of more than 50 percent because, likewise, Argentina will have no chance of taking on debt in the voluntary market again. What is your take?

I don't think Argentina should go back to the capital markets any time soon. This has been a short-term temptation and a longer-term curse for Argentina for decades. I've been involved with Argentina one way or another for the last 40 years, watching from outside as an economist who studies and analyses these issues – how Argentina would come back to the capital markets, fall into another crisis, have to reschedule, return, declare as over the crisis only to have a new crisis hit in short order.

That was the fate of the [Mauricio] Macri administration. After all, it proclaimed a solution, ‘We're back in the markets.’ But this is not really the right way to approach it. The right way to approach this is to really clean up the balance sheets, don't get into another crisis. And I hope that Argentina can manage that.

Before joining Alberto Fernández’s government as economy minister, until last December, Martín Guzmán worked at Columbia University and developed close ties with you. What is your opinion of Mr. Guzmán?

He's a wonderful person, very sincere, a very fine economist. And he operates with great professionalism. I really like that and appreciate that. I think that it's exactly what Argentina should have right now.

You know, there's enough instability all around that I don't think we would be very desirable to have a politician-type finance minister making unbacked statements or outlandish or flamboyant statements or making unreasonable promises.

Mr. Guzman is very measured, very low key, very sincere and serious in analysis. And I hope, I really hope, that this is enough, because the world doesn't need more Trumps and Bolsonaros and this kind of craziness which is all around. We need some sober-headed, realistic ideas about how to move forward. And I think the professionalism of Minister Guzman is exactly what's called for.

What recommendation would you give to him in the renegotiation?

I would say be calm. Be patient. Most of all, attend to Argentina's own internal needs right now, which is to fight the pandemic.

Argentina, unfortunately, is in a region where there's almost no success in fighting the pandemic. Of course, I think Bolsonaro is completely unhinged and irrational – a danger for Brazil and a danger for all of South America. Even Chile is having a very hard time containing this epidemic. Peru and Ecuador have been hard hit. Unfortunately, Mexico is very poorly led right now with AMLO [President Andrés Manuel López Obrador] who is, also like Bolsonaro, trying to minimise the impact of Covid-19. I can tell you none of that makes sense. This is a very serious disease. It's a very serious epidemic. It is very disruptive globally ...

Argentina needs to really be careful right now, contain this epidemic, focus its scarce resources on fighting the disease, on protecting the supply chains and keeping the exports, especially the agricultural exports, going. The world needs Argentina's products, and Argentina needs the foreign exchange income.

I hope and expect that the creditors will come around to a reasonable agreement. But if it doesn't happen this week or this month or next month, I don't think it's any kind of tragedy, frankly. There are enough things to worry about other than what BlackRock or Fidelity are doing right now, which is just not the high priority.

The fact that there are a few investment funds, such as BlackRock and Fidelity, that hold a large part of the debt, does it favour or make it difficult to negotiate?

It's very favourable and very important, because they can actually make a deal. And when they make a deal, they'll carry a lot of the rest of the bondholders along with them. And they should be responsible. A company like BlackRock is not really just a private company. It's almost a state company in the United States. So it is aligned with the US Treasury. It's aligned with the Fed. It manages seven trillion dollars of assets. It's part of the US system. It ought to be thinking systemically – that means responsibly. This is not a game for BlackRock to get an extra percentage point, that's absurd.

Argentina's fate is far more important as a sovereign nation with stability that is not part of breaking up the international finances. So I'm glad that BlackRock is a creditor and a systemic player in the sense that it has a big stake and a big responsibility in holding the international system together. And I know Larry Fink knows full well that he ought to make a deal with Argentina and just get on with it, because it is not of any consequence for BlackRock – whether the interest rate is two percent or three percent or five percent, it means nothing for BlackRock, but it means a lot for Argentina.

And what recommendation would you give to the Argentine government over its relationship with the IMF?

I think the relationship with the IMF right now is very healthy in that there is a strong interchange at the technical level between IMF technicians and Argentine technicians. And since the Economy Ministry is led by a technician, that really helps. And there is the intention by the managing director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, to find a real solution for Argentina. I know that, I've heard her speak on this several times. I, of course, discussed the issues with her and she wants a reasonable solution. I think reason is really the key here. This isn't emotional.

It's not about ‘I deserve this’ or ‘I deserve that,’ or ‘this is fair’ or ‘that's not unfair.’ It's really about finding a solution, based on the data, of what can be done that meets the needs of Argentina and its people and is suitable as a solution for the IMF and the international financial system. And given that interest rates today are between one and two percent for the long term for the US or Europe and for many of the bonds in BlackRock’s portfolio, lowering the interest rates to a point where Argentina really can pay makes reasonable sense.

I hope that Argentina actually would enter some kind of a programme with the IMF – not the one that was put together in a desperate emergency under Macri, that didn't work. It was thrown together very quickly, it was kind of an act of desperation as things were falling to pieces. This one would take place, after all of these dramatic events and I think it's possible, therefore, to find a very helpful and reasonable agreement between the Fund and Argentina that holds things at bay. Whether there is an agreement with the private creditors, for the moment, that should not block good arrangements with the IMF. The IMF knows full well this is not the time for austerity.

Is the influence of the United States in the decisions of the International Monetary Fund decisive?

It's very influential in general, but the US is a really weird situation right now. Of course, we're a few months before an election, our president is not a very stable person, our policy-making is completely unstable in the United States. I don't really know whether they're paying any attention to Argentina at all, frankly, because the real focus is on double-digit unemployment in the United States, mega budget deficits that are trillions of dollars and constant political feuding…

How do you evaluate the management of the current IMF director, Kristalina Georgieva, in general? Is she the right person for this moment?

In general, the management is very good in that the managing director is a very experienced global policy manager. She has been at the forefront of humanitarian crises, she's been at the forefront of European politics, she has been running the World Bank in recent years, in operational terms. And now she is very well placed in this worst global crisis in 75 years since World War II to help steer the IMF. So I'm very impressed and I know that she's very sincere in using all multilateral tools to address this crisis.

From the IMF point of view, remember, there are 80 countries or so that have come for emergency financing already. This is a global emergency that we're facing. Argentina is just one country on a long, long, long list of deep challenges right now. And so it's not the centre of world attention as it might be felt in Buenos Aires. It's why I think that staying calm and focusing on your internal problems is the right thing to do. And managing this global scene is very difficult, especially because Trump is, you know, so unstable that every international institution is watching its back. Who could imagine that the US president would cancel funding for the World Health Organisation at the time of the greatest pandemic in its history? It's mind-boggling.

The last time that I interviewed you was at the beginning of 2018, when Macri was at the helm. But when he was elected president, he was welcomed by the global community as the "slayer of populism," while international investors allowed Argentina to borrow a lot of money. Then, the IMF bailed out the country, presented completely inaccurate economic projections, and saw the country sink deeper into stagflation. How much responsibility do private creditors and the IMF have in Argentina's collapse?

Argentina is by nature a very unstable economy because Argentina is a country of macro-economists – everyone has lived through multiple crises, everyone understands foreign exchange markets, stop-go-stop economics. Everyone understands international financial markets. And so what would be almost overlooked in any other place in Argentina is the makings of a crisis.

I don't think Mr. Macri's policymaking was horrendous in any way, actually. I think it was fine by and large … There was a kind of panic, which is familiar in Argentina. Mr. Macri said the word IMF and that by itself triggered half the collapse because Argentine people know if you say the word IMF: ‘Oh, my God, there is a crisis ahead.’ And so there is a lot that is self-fulfilling in Argentina. It's caught in a trap. It's caught in a Groundhog Day trap.

This is a country that has experienced more crises than any other on the planet with the possible rivalry of your close neighbour, Brazil. But other than that, Argentina really stands on its own. And so, when there are minor infractions of policy – and I think Macri certainly made minor infractions of policy – they become major crises in a way that would not be true in almost any other place on the planet. Macri did not create great economic sins, nobody did. But it’s a country that's ready to move its money from pesos to dollars at a moment's notice, that hears the word of a possible IMF agreement as an invitation to flee the banks as a worry, after so many generations of closing banks or conversions of currency or other things.

This is really the problem. And to my mind, that's why I hope that Argentina can really stay calm and stay patient and go for a real agreement, not a short-term fix that two years later reverts to yet another crisis. I would like to see this current government live out its term without a new round of financial crisis. It's got enough on its hands between the inherited crisis and the Covid epidemic. To just try to find a path to some stability and recovery and to get there will require patience, forbearance, some social unity, which is very hard in the Argentine context, because not only is it crisis-prone, it is so politicised that each turn of politics becomes an occasion for another self-fulfilling crisis.

The accusation against Macri's government is the amount of debt – he increased the debt in three years in the same amount of debt that Argentina had accumulated in the past. Is this irresponsible or not?

I don't think that the gradualism that he adopted, funded by international markets, was all that prudent – I don't think it was all that unusual, by the way, it wasn't extreme – but under Argentina's history, I think certainly, in retrospect, there's no doubt to say that the fiscal consolidation should have gone farther and faster.

When the IMF emergency programme was put together, incidentally, I had no confidence that it would actually work, and that isn't an ex-post judgment, that was looking at it at the time. It just seemed to me that it was a kind of desperate move. I think there was politics involved also, with the US hoping to keep Mr. Macri in power. And so it was throwing a programme together that, to my mind, didn't have much credibility or careful design. It was sudden. It was under urgency. It was in the face of a panic, knowing that an election was coming up.

I didn't think it was going to work, and I've said so, and it didn't work. And so there's enough that one can say, yes, the borrowing should have been less. This urge to return to the capital markets is always exaggerated, in my opinion. The focus on the capital markets rather than on deeper issues of productivity, science, technology is a chronic issue. Argentina's future, in any event, doesn't depend on the capital markets. It depends on becoming more productive, more technology based, these are deeper changes that are needed in the economy.

You wrote a book, Escape the Curse of Natural Resources, with Joseph Stiglitz. Is that Argentina’s curse too?

Argentina is such a complicated history that it's hard to identify exactly one problem, except for the fact that crises became the problem. Just the history of crisis itself has made Argentina crisis-prone because of their self-fulfilling nature.

Why Argentina fell into that crisis is, of course, the matter of long debate of economic historians. I've spent time studying that question. Of course, it does go back to the 1930s, with the Roca-Runciman treaties, it goes back to the protectionism of the British Empire, it goes to all of the instabilities of the 1940s and 1950s. You could date it, of course, to preceding Argentine history, social inequalities, instability and to subsequent history. The recent history of many financial crises. But I think that the way out is another matter.

The way out, I would say, does depend on Argentina and Latin America in general, moving to a much more diversified and technology based economy and society rather than the base of the rich, pompous and the vast natural resources that have been the lifeblood of South America's economy for 500 years. And so in this sense, the idea of the resource curse does resonate – it doesn't explain everything about Argentina's history, but it does point to a current fundamental fact. And it's something that I've felt very powerfully throughout my career and experience.

When I go to Asia, all the talk is about technology. When I come to Latin America, the talk is about culture, politics, society, but rarely about technology. And so there's really a difference of organisation and perception. Latin America is the region of lawyers, novelists, dramatists and psychiatrists, and Asia is the region of engineers. And I think it would not hurt to have some more engineering in Argentina. I mean, heaven knows Argentina's produced some of the world's great scientists, often doing their science in other places, sometimes in Argentina, but not really the roster of leading engineers in history. And yet economic development is so much based on engineering. And I think that this is a missing part of Latin America's strategy that goes back to its resource endowments and the vast wealth of the country.

One of your iconic books is The End of Poverty and you were a special advisor to the United Nations on sustainable development. There are countries that were poor and managed to get out of poverty, while others couldn’t. But there are not many cases about countries that were rich and became poor, such as Argentina.

Actually, Argentina is not a poor country. It's got some poor people, for sure. But it is not a poor country despite all of the crises of the 20th century. After all of the disasters, Argentina is not a poor country, and partly it's got such a good, astounding, rich natural inheritance that it's almost impossible to be a poor country.

It's interesting, by the way, another country that now really is a poor country in South America is Venezuela, but that's partly because of very bad policies by [Hugo] Chávez and [Maduro. And it's partly because of the absolute cruelty of the United States in trying to overthrow Maduro by crushing the Venezuelan economy. So that's a different matter. That's a case of deliberate impoverishment at the hands of US sanctions.

Fortunately, Argentina is not in that category. I think, you know, if you go back to what we were just discussing on the resource curse, Argentina became wealthy in the early 20th century on the basis largely of agricultural exports, which were so productive, both the grains and meat products, that it made Argentina one of the rich countries of the world in per capita terms. The Great Depression was the end of that model of development, but not the end of Argentina's focus on agriculture as the core of its export industry, and so famously, Argentina became inward-protectionist, partly in response to the new protectionism that Britain entered in the 1930s in very adverse forced treaties with Argentina and the protectionism in the world in the 1940s and 1950s. But even during periods of opening international trade, once again, I would say Argentina is a rich, prosperous and very literate population. Strangely, it didn't become a global leader in new technologies ...

I would like to see Argentina think carefully and society-wide, and not in a typical political conflictual way, about what Argentina can and should look like in 30 years. Because that would, I think, reorientate it in a useful way. Argentina's investments in its people, in technology, in choice of industry and so forth. I mean, even to this moment, Argentina is putting its new hopes in new natural resources, in new natural gas deposits, for example. I regard this as ridiculous because the whole world's trying to get out of carbon. Hasn't Argentina heard? Don't go deeper into carbon. We've got more oil and gas than the world could ever safely use. How could Argentina base its future on that? When you have so much wind power, solar power, or hydro power, but yet Argentina wants to double down on new natural gas deposits, on fracking and other things in the midst of this oil glut in the world. So I think that thinking ahead technologically is always a good idea, but it's especially a good idea right now because we're moving to a worldwide digital renewable economy. And that's where the exports are going to be. That's where the income earnings are going to be. That's where the new leading edge sectors are going to be. And Argentina, of course, can play an important role in that – but it takes a decade of investments that are directed in that way.

Today in Argentina, a special tax on the country’s 12,000 richest people is being discussed as a contribution to alleviate the coronavirus crisis. What do you think of wealth taxes?

It's a good idea. People with wealth should pay more. And this is true in the United States. And it's true in Europe. It's true in New York City – the wealth is extraordinary, about fifteen Americans have a trillion dollars of net worth. One trillion – my God. And that has soared in recent years. And most of it, Or all of it in some cases, is sheltered. They hardly pay a cent on it. And this is just no way to organise a decent society. And when the Covid epidemic hits, we don't have social solidarity. We don't have a government that can function because in a plutocracy, nothing functions properly. I'm going to have to finish shortly.

Jeffrey, thank you very much for your time. I hope to interview you again in the future in Argentina.

I look forward to it, always.

Comments