La grieta, Argentina's famous (or should it be called infamous?) political rift, has not gone away during the coronavirus crisis.

For the centre-right opposition, the country's economic collapse is a result of the lockdown measures first introduced by President Alberto Fernández, the country’s centre-left Peronist leader, on March 20. To government supporters the pandemic, not the quarantine, is what’s to blame (as well as the preceding government, as they like to keep reminding everyone). Both camps agree that the economic situation is bad and the constant arguing will probably make it worse. The data is dire: the economy plummeted 19.1 percent in the second quarter, while unemployment has increased to 13.1 percent, the highest since 2005 (even with dismissals formally banned). Many now compare the situation with the devastating economic meltdown that Argentina suffered in 2001 after a huge default.

Economy Minister Martín Guzmán recently managed to produce some good news: he successfully restructured US$65 billion worth of foreign debt. Yet suddenly the Central Bank has now announced the tightening of foreign currency controls, despite dollar purchases already being limited to US$200 a month. The Central Bank has scrambled to increase the red tape to crack down on loopholes in the monthly dollar purchase cap, amid fears that foreign currency reserves are running out. The new measures, which have effectively all but frozen dollar purchases while private banks deal with the new technicalities attached to the limits, have left Guzmán in a tight spot. After all, the minister and US-trained economist had implied in a Sunday newspaper interview that there would be no further controls on top of the US$200 limit, which was introduced originally by the struggling administration led by centre-right president Mauricio Macri.

Government officials are now urging the public to save in pesos. The president declared that dollars are needed for production. One minister said that properties should no longer be bought and sold in dollars. Yes, you’ve heard it all before. What is relatively new is the extreme agitation unleashed by a sector of the opposition, which at times brandishes the government as authoritarian.

The opposition, for example, has fiercely criticised a recent vote in the Senate, controlled by Vice-President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, that forced three judges to leave their current positions, to which they were appointed by a decree from Macri. The ruling party argues that the appointments were irregular, but the Senate vote has infuriated the hawkish sector of the opposition. The government says that the judges lacked the mandatory Senate approval to move from one position to another. But here’s the key point: the three judges were handling high-profile corruption cases involving Fernández de Kirchner. A small but defiant demonstration was held outside Buenos Aires City’s central courthouse on Wednesday night. The problem for the government is that it can't organise street demonstrations in its support – that would be in breach of the coronavirus restrictions it promotes.

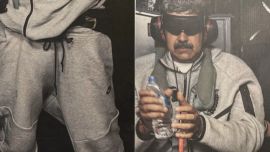

Will this relentless agitation unleash the kind of volatility that rattles the very standing of the government, less than a year after winning the elections? A recent mutiny to demand pay increases by the Buenos Aires Province police included an ugly protest outside the Olivos presidential residence by armed police officers and patrol cars. The mutiny, which ended after a pay increase was announced, triggered speculation about infighting in the ruling coalition between the Peronist mayors and provincial Security Secretary Sergio Berni, who brags that he takes orders only from Fernández de Kirchner (the leader of the powerful Kirchnerite wing of the ruling coalition). Berni preaches law and order and has political ambitions, which don't necessarily go down well with the Peronist mayors who are used to controlling the territory in Greater Buenos Aires, the sprawling poverty-ridden urban belt that surrounds the capital. The provincial police top brass has now been reshuffled.

The mutiny ended when the president announced a sudden reduction in the federal revenue pie awarded to Buenos Aires City. The cash will be used to significantly improve provincial police salaries, Fernández said. Buenos Aires City Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta has taken the case to the Supreme Court.

Rodríguez Larreta is a key moderate leader of the centre-right opposition who has not backed the anti-government street demonstrations and has worked with Fernández and Buenos Aires Province Governor Axel Kicillof, in a show of bipartisan civility during the pandemic. But now Fernández and Rodríguez Larreta, who is performing well in polls and is a potential presidential candidate in 2023, are at odds over the revenue snatch.

The question that few are posing in public is if the agitation amounts to what in the past (before the fake news era kicked in with such fury) was referred to as ‘coup-mongering’ against a democratically-elected government. The president's popularity is dropping in the polls. The ruling coalition is trying to push a wealth tax bill through Congress, further exasperating the opposition and business lobbies.

The pressure is once again on Guzmán, who on Wednesday submitted next year's budget to Congress. The economy minister is now formally in charge of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reschedule pending payments from the US$44 billion injected by the Fund into the country during the Macri presidency. An IMF mission team will visit Argentina next month as talks begin in earnest.

Perhaps the pressure is telling. Guzmán, who had kept his cool during the exasperating negotiations with the bondholders, on Wednesday suffered a slip on unveiling next year's budget in the Lower House of Congress. Unaware that his microphone was picking up what he was saying, the minister told Lower House Speaker Sergio Massa that he could fill any awkward silence due to technical problems with meaningless chatter. Guzmán later tried to explain himself, but it was an unexpected gaffe by a minister who has measured every step he has taken so carefully. The challenge for him now is not to stumble when other members of the administration seem to be taking their economic recipes to the president, without going through the Economy Ministry first.

Comments