Martín Guzmán was the previous week’s star minister beyond any dispute from the afternoon of April 16, when he presented Argentina’s offer to creditors. My immediate instinct was to shelve my already completed Labour Ministry column and scramble something together in the 30 hours remaining before publication. But for a start that column would have missed the fine details presented to the Securities & Exchange Commission in the United States late on the Friday, not advancing beyond the Thursday broad bones – no regrets and no apologies, then, even if this column is a week late.

President Alberto Fernández and others are fond of speaking of a “false dilemma” between public health and the economy, a logic which takes on a whole new meaning when applied to the debt context. While governments worldwide are finding that dilemma anything but false, there is a curious win-win situation for Argentina within the coronavirus pandemic catastrophe.

Covid-19 covers a multitude of sins – not only the perfect alibi for an inability to keep populist campaign promises to snap Argentina out of its negative economic spiral but also an ideal setting for debt hardball. Lockdown might seem the wrong time for any serious debt negotiations but is in fact the best time for the Fernández presidency since the inability to pay is beyond debate – the lower current bond quotations, the lower the eventual exit yield needs to be to look acceptable. Without hatching any absurd conspiracy theories or questioning the medical wisdom of quarantine, lockdown overkill also includes some economic benefits which favour its continuation.

The offer was described at the time as a “virtual default” by President Fernández (the credit rating agencies quickly agreed, giving Argentina a “C” on the brink of default). How close to default are we? Technically speaking, the clock is ticking up to May 22 when the grace period for the Global bonds (around half a billion bucks) not paid last Wednesday runs out.

Many expect frantic negotiations in the intervening period but that might not happen. Guzmán has the mentality of an academic, not a negotiator – he has done his homework on this unilateral offer, which is the fruit of econometrics not haggling (a prime complaint of creditors). So when he repeatedly says that it is “final,” perhaps he means it.

Whether there is indeed finality or whether this is an opening bid with sweeteners (such as growth-linked bonds) to come to break the ice will perhaps hinge on how deeply President Fernández fears default, of which he has personal experience – whether it would doom his government to failure by killing public-sector credit and private investment alike, along with export guarantees and thus trade and any growth in an economy without domestic savings, or whether he feels he has nothing to lose, with no investments coming

Argentina’s way anyway, as Guzmán has pointed out (with nothing more than a drizzle even for a market-friendly Mauricio Macri forecasting rain), not to mention the political attractions of demonising vulture funds.

But if “take it or leave it” remains Guzmán’s attitude, takers are looking thin on the ground. Such major investment funds as Greylock, Ashmore, BlackRock and Fidelity have all said no although not averse to negotiations further down the road with Argentina not so broke and reasonably expected to pay something – choosing such a bad moment is seen as the opposite of the “good faith” Guzmán likes to profess.

What especially irks investors in the Guzmán offer is the three-year grace period, far more than the haircuts (a 62 percent scalping for interest payments and a 5.4 percent trim for capital) – no payments on principal are offered until 2026 (with the bond swap instruments falling due between 2030 and 2047) when annual interest payments alone would pay over a year of pensions. A shorter term for coronavirus debt relief would be acceptable but nothing until a meagre US$300 million in 2023 is pushing it. Creditors see no will to share the pain now and no plan for paying in the future, feeling Argentina can do better when its problem has always been liquidity rather than solvency.

A broad menu of bond swaps does offer multiple options for those giving priority to collecting sooner even if less or receiving more later but always within the bottom lines of nothing until 2023 and around US$40 billion off the US$66 billion under foreign jurisdiction (with local dollar bonds of US$10 billion already suspended for this year). But no space for further detail – time to meet the minister.

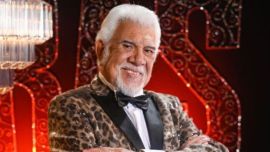

Born on Columbus Day (in the Buenos Aires provincial capital of La Plata, whose University gave him both an undergraduate and masters degree in economics), Martín Maximiliano Guzmán, 37, would locate his professional umbilical cord in New York’s Columbia University (even if his first postgraduate studies were at Brown).

At Columbia, his tutor and mentor was the 2001 Nobel Economics Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz, under whose wing he became an Associate Research Scholar at Columbia Business School and came to advise the United Nations General Assembly on restructuring sovereign debt. That latter field is the exclusive reason for his appointment and his main focus as minister, with most other aspects of the economy handled by his Production colleague Matías Kulfas – the initial favourite to head the Economy Ministry alongside current Deputy Cabinet Chief Cecilia Todesca.

Indeed, Guzmán only entered the running for the post just six weeks before the Cabinet was named, when paying one of his quarterly visits to Argentina in the penultimate week before the October elections. While the title of his La Plata thesis “Pro-cyclical fiscal policies in volatile contexts” might sound like the purest Kirchnerismo (prophetically so since presented in the year of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s inauguration, 2007), one of his ministerial predecessors, Roberto Lavagna, took a different view according to last week’s interview with President Fernández, saying: “He has the necessary dose of heterodoxy and the indispensable dose of orthodoxy.”

The Economy Ministry itself is nominally the subject of this column but not much space left. One of the quintet in the original 1854 Cabinet, this portfolio has gone under eight different labels since then with 111 ministers (of whom no less than 17 repeated), averaging a tenure of 18 months ranging from five days (Miguel Roig in 1989) to 74 months (Domingo Cavallo). Especially in the last century, various ministers have been defining figures in Argentine history with Federico Pinedo (1933-1935) perhaps the first – Ramón Cereijo, Alvaro Alsogaray, Adalbert Krieger Vasena, José Ber Gelbard, Celestino Rodrigo (in just six weeks!), José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, the late departed Roberto Alemann, Cavallo and Lavagna.

It remains to be seen if Guzmán joins these famous and/or notorious forebears or will be just another name in a long list.

Comments