Some fight in Yemen or Afghanistan, others guard oil pipelines in the United Arab Emirates; and yet more turned up in Haiti this week, where they are accused of assassinating the president.

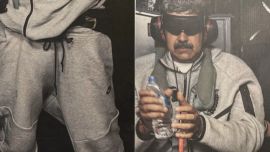

Hardened by more than half a century of conflict back home, retired Colombian soldiers and illegal combatants feed the sinister market of mercenaries around the world.

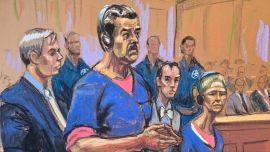

Some 26 Colombians have been accused of taking part in the pre-dawn murder of president Jovenel Moïse on Wednesday that also left his wife Martine wounded.

Colombia said on Friday that at least 17 ex-soldiers are believed to have been involved in the attack at Moïse's home. Some were killed by Haitian police and the majority were captured.

But the participation of Colombian mercenaries highlights the lucrative transnational mercenary market.

"There is great experience in terms of irregular war... the Colombian soldier is trained, has combat experience and on top of that is cheap labour," Jorge Mantilla, a criminal phenomenon researcher at the University of Illinois in Chicago, told AFP.

It's not just retired soldiers that leave Colombia's borders – already so porous to the export of cocaine – as guns for hire.

In 2004, Venezuelan authorities detained "153 Colombian paramilitaries" they accused of taking part in a plan to assassinate then-president Hugo Chávez.

'Prey to opportunities'

Colombia has a seemingly inexhaustible pool of soldiers. The Armed Dorces are made up of 220,000 personnel and thousands retire over a lack of promotion opportunities, misconduct or after reaching 20 years of service.

Every year "between 15,000 and 10,000 soldiers leave the army rank and file... it's a human universe that is very difficult to control," Colonel John Marulanda, president of a Colombian association for former military personnel, told W Radio.

They retire relatively young with low pensions and that makes them "prey to better economic opportunities," said the retired officer.

He says that what happened in Haiti was a "typical case of recruitment" of Colombian ex-soldiers by private companies to carry out operations in other countries.

Colombian authorities say four companies were involved in the assassination.

A woman who claimed to be the wife of Francisco Eladio Uribe, one of the captured Colombians, said a company offered her husband US$2,700 to join the unit.

Uribe retired from the Army in 2019 and was embroiled in the "false positives" scandal investigated by authorities, in which soldiers executed 6,000 civilians between 2002 and 2008 to pass them off as enemy combatants in order to gain bonuses.

Mercenary industry 'boom'

In May 2011, The New York Times newspaper revealed that an airplane carrying dozens of Colombian ex-soldiers arrived in Abu Dhabi to join an army of mercenaries hired by the US firm Blackwater to guard important Emirati assets.

The Times then claimed in 2015 that hundreds of Colombians were fighting Houthi rebels in Yemen, now hired directly by the UAE.

For the last decade "there's been a boom in this industry," said Mantilla.

At that time, the United States began substituting its troops in the Middle East for "private security firms because it implies a lower political cost in terms of casualties and a grey area in international law."

When it comes to potential human rights violations "the legal responsibility falls on the material perpetrators" rather than the State or company that contracted them, said Mantilla.

Today there is a global market in which US, British, French, Belgian or Danish companies recruit mercenaries mostly from Latin America or countries like Zimbabwe or Nepal that have had armed conflicts.

"The companies are legal, but that doesn't mean that all the activities carried out by these people are strictly legal," added Mantilla.

by Juan Sebastián Serrano, AFP

Comments