The International Monetary Fund’s record loan to Argentina last year was supposed to turn the page on a troubled history. It’s looking more like a case of déjà vu.

Less than two decades ago, Argentina crashed out of an IMF programme, defaulted on debt and plunged into depression. As Fund officials arrived in Buenos Aires over the weekend to assess the country’s current US$56-billion bailout – and decide whether to keep doling out cash – some of the same warning signals are flashing.

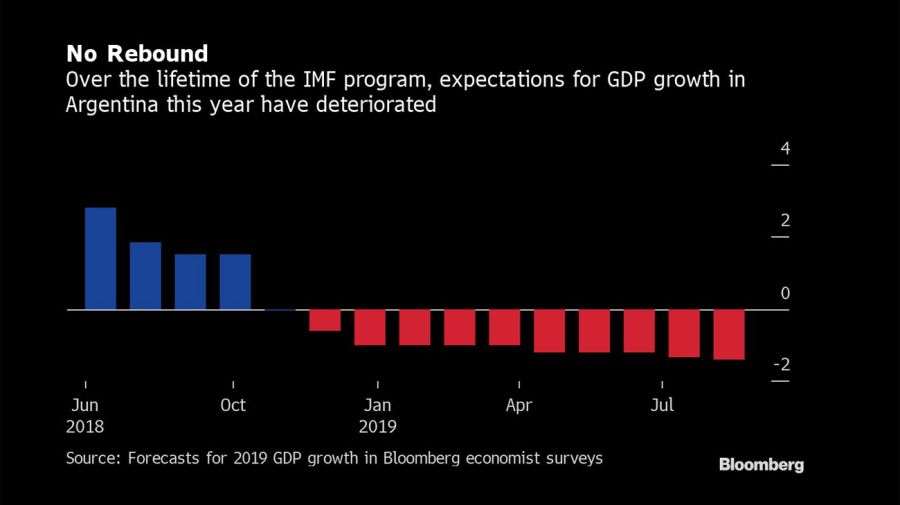

President Mauricio Macri just got trounced by the populist opposition in a nationwide primary vote, after his IMF-backed programme – based around budget austerity and the world’s highest interest rates – failed to pull the economy out of recession.

His defeat cued a market rout that was spectacular even by Argentina’s standards of volatility. The peso slumped 20 percent in a week, and yields on government bonds surged -– pushing the implied risk of default above 80 percent.

Cough up?

The IMF delegates, who arrived in Argentina on Saturday and immediately began meetings with policy makers, face a tricky choice with unwelcome echoes from two decades ago: risk making the turmoil even worse by withholding a US$5.3-billion installment due next month – or cough it up, even though the programme’s future looks highly uncertain.

They’ll also have to figure out the economic plans of opposition chief Alberto Fernández – who’s likely to head a less market-friendly government. The IMF team will meet Fernándezz’s economic aides later on Monday. While elections are still two months away, Macri’s 15-point primary defeat has led analysts to write him off as a lame duck.

“The IMF has put a lot in – not just money, but prestige,” said Héctor Torres, a former executive director at the Fund who represented South American countries.

“The fact that the arrangement is not performing well right now is an embarrassment,” he said. And the September installment is “going to be a difficult call.”

Until this month, Argentina was roughly on track to meet an IMF target of balancing the budget this year (excluding interest payments). The Fund may cite that performance in the first half of the year as grounds for handing over next month’s payout, according to Priscila Robledo, Latin America economist at Continuum Economics in New York.

“That’s what I think will be the justification: ‘Nothing happened at the end of June, we’re all fine’,” she said.

‘Won’t be met’

Since the ballot reverse, Macri’s government has begun to loosen policy. It froze fuel prices and boosted subsidies, in an effort to shield the poorest Argentines as the peso’s latest slide threatens to push inflation even higher.

Fitch Ratings now predicts a primary deficit of one percent, though the government still says it will meet IMF budget targets.

“The Fund might say its evaluation going forward is that they won’t be met,” said Daniel Marx, who negotiated with the IMF two decades ago as Argentina’s finance secretary, and now heads research company Quantum Finanzas in Buenos Aires. In that case, “the disbursement could be at risk.”

The Central Bank could also breach IMF targets, as it burns through cash to defend the peso, Marx said. “Now that they’re starting to intervene in spot markets, that might affect net reserves.”

The bank managed to steady currency and bond markets last week. But debt due after 2028 trades below 50 cents on the dollar – a potential red flag for the Fund.

‘No possibility’

The IMF has special criteria, which it tweaked after the Greek crisis, for jumbo loans like the one Macri got – and compliance is reassessed at each review. Two of them are key for Argentina right now: the Fund has to be satisfied that a borrower’s debt is sustainable and that it has decent prospects of access to private capital.

Judging by the markets, Argentina may struggle to meet those benchmarks. That opens a range of possibilities, including what the IMF calls “reprofiling” – an extension of debt maturities, with few other changes – or the kind of restructuring brokered by the Fund for Ukraine in 2015, which involved haircuts too. IMF officials declined to comment for this story.

Fernández, who trumpets his experience working with the IMF as Cabinet chief in the years after the 2001 crisis, insists that there’ll be no replay. “There’s no possibility that Argentina will fall into default if I’m president,” he said on Wednesday.

Fernández has been vague about policy commitments and says talks with the IMF are Macri’s responsibility while he’s president. The opposition chief has said the programme must be revised to allow Argentina to grow again.

‘Some dorm of haircut’

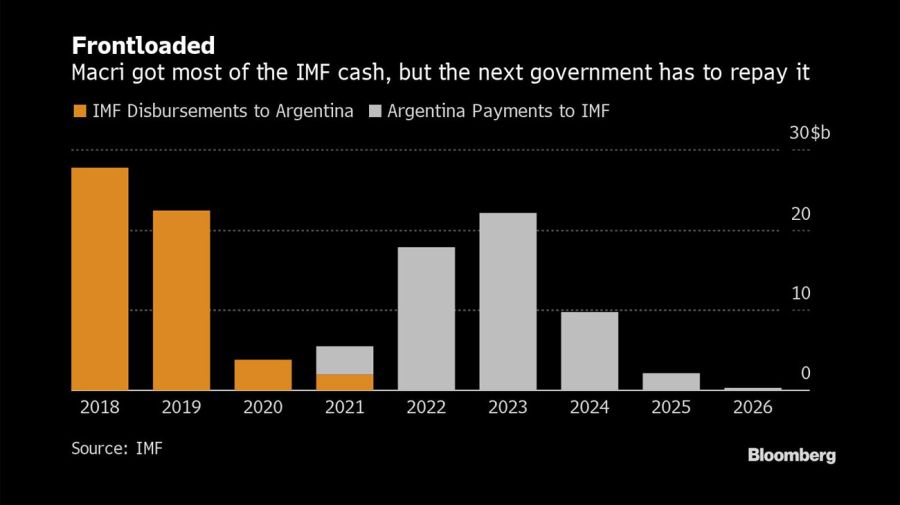

He’ll likely start by arguing that Argentina, with bills coming due to private creditors too, will need more time to repay the Fund, said Patrick Esteruelas, head of research at EMSO Asset Management in New York, which oversees about US$6 billion.

“Fernández’s first request will be to reschedule,” Esteruelas said. If a deal can’t be hammered out, “private sector debt holders would have to take some form of haircut.”

Ordinary Argentines also have traumatic memories of failed IMF programmes. Many blame the Fund for the epic collapse of two decades ago, one reason why Macri’s decision to go to the IMF last year was so risky.

Late in 2001, after a series of missed budget targets and re-upped IMF loans, the government announced it was preparing to restructure debt. Argentines rushed to the banks to pull their money out – and found their deposits had been frozen by authorities, an event known as the “corralito.”

A week later, the IMF finally pulled the plug, declining to disburse more funds. Mass protests erupted, leading to dozens of deaths. The political system convulsed, with four presidents succeeding each other in the space of a month. In the longer run, Argentina was frozen out of world markets for over a decade, and millions saw their savings wiped out.

‘The bank’s problem’

Most analysts say things aren’t that dire today – including Alberto Ramos, who was on the IMF’s last trip in 2001 as an economist.

Argentina has done a better job this time of sticking to its program, and “without the IMF we would be talking about a much more difficult situation” said Ramos, now chief Latin America economist at Goldman Sachs. But he said the country’s turbulent history means there’s always a risk of social panic. “That’s another layer of difficulty to this.”

Another one is the prospect of an extended transition of power. There’ll be a four-month gap between the August 11 primary and the swearing-in of a new government. And the Fund has its own leadership vacuum: Christine Lagarde, the IMF chief who signed off on Argentina’s loan, is in transit to the European Central Bank and may not be replaced for weeks.

“The IMF is in a serious pickle,” said Esteruelas. “It reminds me of the saying: If you owe the bank US$100, it’s your problem. If you owe the bank US$100 million, it’s the bank’s problem.”

related news

by Carolina Millan & Patrick Gillespie, Bloomberg

Comments