Four months into office, Argentina's President Javier Milei has pulled off a critical feat in a country long ravaged by runaway inflation: he stabilised the currency.

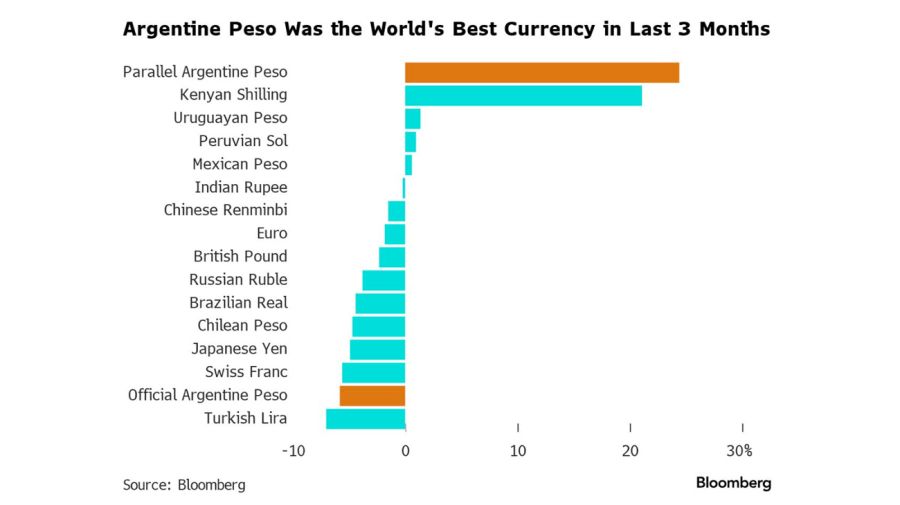

The peso has, in fact, not only stopped plunging day after day but in one key foreign-exchange market — there are many of them here, a byproduct of the country’s web of byzantine rules — it’s actually rallying sharply. The peso has soared 25 percent against the dollar over the past three months in the market, known as the blue-chip swap, that is used by many investors and companies. That’s more than the gains posted by any of the 148 currencies that Bloomberg tracks against the dollar.

It’s a shocking statistic in a country where the currency is seemingly in a never-ending state of free-fall. (The smallest annual decline in the past decade was 15 percent.) And it underscores the lengths that Milei has gone to to rein in bloated government spending, choke off demand for everything in the economy, including dollars, and tame inflation that’s skyrocketed to an annual pace of almost 300 percent.

Milei likes to call his budget cuts “the largest in the history of humankind.” This is almost certainly an exaggeration, of course, but not by much. The cuts he imposed add up to the equivalent of almost four percent of the country’s economic output, an adjustment so aggressive that Central Bank officials estimate it’s larger than 90 percent of all those carried out in the world over the last several decades.

There are dangers, to be clear, everywhere for Milei and his strong-peso policy. For one, the spending cuts have sunk the economy into a deep recession. And as Argentines who have already been squeezed by inflation lose their jobs, the political pressure to scale back his fiscal program will mount, analysts warn. He has been forced to rely on stop-gap measures to gut the budget because his broader reform package has run into resistance in Congress, a sign of how politically tenuous his economic plan is.

“The great novelty in Argentina is that the person in charge is not worried about paying the political cost that comes with austerity — that’s unusual,” said Javier Casabal, head of research at AdCap Grupo Financiero in Buenos Aires. “The government’s goal will continue to be to break the back of inflation.”

Which leads to the next big risk: that inflation doesn’t come down as quickly as Milei’s team envisions.

Not only would this anger Argentine consumers, it would further increase the value of the currency in inflation-adjusted terms. Since the peso first began to stabilise in January, it has advanced some 72 percent after adjusting for inflation, a gauge that Argentine investors watch closely because it measures changes in the currency’s actual purchasing power.

Those gains are beneficial for a country until they get to the point where they discourage companies from exporting products and keep foreign tourists away. There are already rumblings this is beginning to happen in some sectors.

“When exporters stop selling,” said Melina Eidner, an economist at PPI, a brokerage in Buenos Aires, “the parallel peso weakens.”

For now, though, it continues to gain. On some days this year, it’s jumped as much as four percent. Even in the official market, where most big import-export transactions take place, the peso is largely stable. Policymakers guide it slightly lower each day — about 0.05 percent or so — in a heavily regulated system designed to smooth out fluctuations.

The peso is holding up so well now that the central bank has been able to step into the market on a daily basis to buy dollars and replenish critically low hard-currency reserves. This is a telltale sign of just how out of step Argentina is with global markets; central bankers across much of the world now are doing, or considering doing, the exact opposite in an effort to shore up their currencies against the dollar.

Some of the supply-and-demand dynamics in Argentina are a result, critics point out, of the fact that Milei has left the currency restrictions he inherited in place. But those rules did little to slow the peso’s collapse in the blue-chip swap market before he took office.

What’s different now is that Argentines, for the moment at least, have more confidence in the peso, curbing demand for the safety of dollars. And with the budget cuts in place, the central bank is no longer directly financing government spending by printing money, bringing an end to a constant source of pressure on the currency.

“Under this government, economic policy is starting to become rational,” said Carlos Perez, director of the consulting firm Fundacion Capital. Plus, Perez notes, many people who had shifted spare cash they had into dollars are now being forced to sell those dollars back to come up with the pesos they need to pay for day-to-day items after inflation spiked. “Their salaries don’t go far enough,” he said.

Milei unleashed that surge in inflation back in December by taking painful — but in his eyes, necessary — steps to free up the economy. He removed some of the price controls that artificially held down inflation and he allowed the official exchange rate to plunge toward the rate set in the blue-chip swaps market.

That he’s now overseeing a torrid peso rally is an ironic twist for a man who had deemed the currency so worthless on the campaign trail that he likened it to “excrement” and said it should be scrapped entirely.

The question is how long he can maintain this new-found stability. To Casabal, at AdCap, there should be smooth-sailing through at least July. After that, he’s less sure. He worries about politics and the pressure Milei could come under.

“Political fragility in Argentina,” Casabal says, “can disconnect you from fundamentals and trigger a spike in the exchange rate.”

related news

by Ignacio Olivera Doll, Bloomberg

Comments