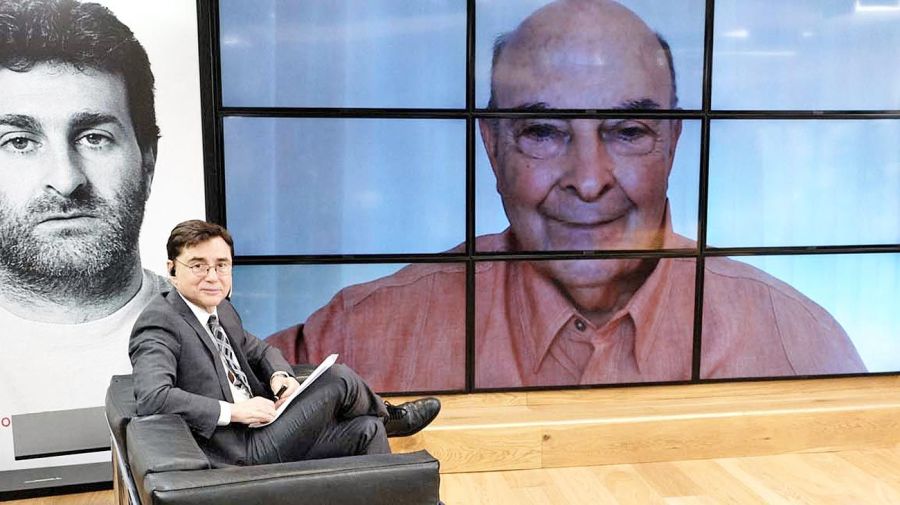

From the United States, Domingo Felipe Cavallo speaks of a “completely disorganised” Argentine economy. He points out that an opportunity to get on track could exist after the elections to the degree that society “gives a clear signal.”

The 74-year-old – a former economy minister, foreign minister, Central Bank governor and lawmaker – analyses the flickers of inflation in the United States, comparing it to Argentina’s stagflation and saying that hyperinflation could come before 2023. In a more immediate term attention should be paid to the gap between the official exchange rate and the ‘blue’ dollar, he warns.

On your blog you wrote: “The government has decided to use three electoral weapons which are very dangerous: increasing public spending, upping wages, pensions and other social benefits above inflation and holding down devaluation of the official exchange rate to just one percent monthly by using the reserves accumulated thanks to the trade surplus from the high soy prices and other exports to narrow the gap with the semi-free exchange rates (CCL and MEP), thus preventing the surge of the parallel dollar last September from being repeated before the elections.” And you continued by saying that market operators forecast that “the accumulated pressure will end up in an explosive devaluation.” What is your own forecast of what will happen?

I prefer not to forecast. I don’t want my forecasts to turn into self-fulfilling prophecies, given that many people pay attention to what I say. Maintaining stagflation without it spiralling into an explosive hyperinflation is something the government will be able to do, both this year and also possibly the next. I’m not very sure that they can succeed in avoiding hyperinflation before the 2023 elections.

This analysis lacks a very solid base, that’s my impression. My objections to the way the government handles the economy do not refer so much to the cyclical as to their economic organisation. Each decision they take means regressing from the progress of the 1990s, some of which was maintained in the following decades. Our economy is very badly oriented. Short of a major reorganisation of the economy, we shall not grow again – we will remain stagnant and with dollar inflation.

The economist Marina Dal Poggetto has warned that instead of buying dollars in the second half, the government will be obliged to sell them. Would that be the turning-point forming the basis for market forecasts?

They surely will be selling instead of buying, that economist is right. But the danger is a run on the fixed-term deposits of the banking system towards the dollar. That would complicate the government’s life greatly. The Central Bank in that event would raise interest rates in a bid to control that situation but nobody is sure how that would work out and I would prefer not to make a very precise forecast.

There is concern among economic agents as to what could happen with the dollar. The Central Bank decides the official exchange rate. The blowout could occur in the free markets, especially the so-called ‘ blue.’ If people think that it suits them to take out their fixed-term deposits and buy dollars on the parallel market, that is a very dangerous run which the Central Bank will have to stop. The only way is by significantly raising interest rates.

Former Central Bank governor Juan Carlos Fábrega has forecast that after next November’s elections there will be a 15 to 20 percent devaluation of the official exchange rate. Does that seem reasonable to you?

If there is not a run after the elections, the government is going to have to explain what kind of economic policy will be followed. Adjustments of the official exchange rate cannot be ruled out. If things go badly [for them], which is something I hope happens because I think it would be good, they will be obliged to reshuffle the Cabinet. And we’d have to see what orientation is given to the economy.

Now poor Martín Guzmán has to manage the cyclical together with Central Bank governor Miguel Ángel Pesce without any clarity as to what economic organisation and horizons the president and the government have in mind. They debate in the face of the specific stances over determined issues which basically emerge from the Instituto Patria and the vice-president’s inner circle. If this continues to happen, the outlook would be very bad for Argentina.

If the government receives a strong signal that things are going wrong, it might just see itself obliged to shuffle the Cabinet and change its orientation but we don’t know what it will do.

Fábrega’s calculation is really pretty simple as the correction of a one percent monthly devaluation when there is three percent inflation, which would accumulate a lag of 15 to 20 percent by the end of the year, give or take.

Yes, but the best way of seeing whether there is a major exchange rate lag or not is to look at the lag. It also depends a lot on what is done with taxation. The more emphasis placed on export levies, the more significant the exchange rate lag will be. If export duties are corrected, the lag will not be so great. The exchange rate reflects the expectations as to fiscal and monetary management.

It’s not easy to talk about and measure the exchange rate lag in circumstances such as these. We must define the kind of economy towards which we are advancing. For example, if we move towards a free economy integrated with the world without capital or price controls, in that case the market will fix the exchange rate at a different level to the current disorganised economy.

What did you think when Cristina Fernández de Kirchner said that we have to face the problem of Argentina being a bi-monetary economy for once and for all? Could her thinking be evolving towards a form of convertibility for the country?

She is suggesting the prohibition of any kind of transaction, not only financial but also commercial and even the circulation of physical dollars. Given the way of thinking of those around her, I don’t believe they are thinking of clearing the use of the dollar as an alternative currency to the peso, the efficient bi-monetary model which Peru has, for example, and which Argentina also had with convertibility.

Argentina fixed the exchange rate while in Peru the bi-monetary model worked without a fixed exchange rate. They achieved exchange rate stability through good management of monetary and fiscal policy in that country. Now there’s a change of government. Many people are very scared as to the positions which might be taken by Pedro Castillo, who is apparently the president-elect of Peru. But they have sent out one good signal by confirming Julio Velarde, who has been running the Central Bank very efficiently since 2000. That was a good decision. Over and above Castillo’s ideas in other aspects – and we’ll see if they are really transformed into government decisions afterwards) – it’s a good sign. He does not want to let go of a monetary system which has assured stability for Peru.

When Cristina Kirchner talks about the bi-monetary problem, she does so thinking of banning the use of the dollar in every kind of transaction outright. She wants people to be compelled to use the peso. Would that someday all we Argentines could feel much more comfortable dealing in pesos. That will come when the necessary measures so that people can trust have been adopted. That’s a very long process. If monetary people were well handled, it would be easier to convince people that the peso is a good currency by stabilising its exchange rate. It’s an issue which can only be discussed when a government has very clear ideas, which is not the case. Talking of a monetary system different to the current is unhelpful.

With Argentina’s economic history, it would seem plausible that even with dollarisation, there would remain the suspicion that a president could order the confiscation of all dollars and their conversion into pesos from one day to the next.

The monetary system always falls integrally into the framework of the overall economic system. You cannot work on the monetary system independently of the other reforms. If in the 1990s we hadn’t advanced towards opening up the economy, eliminating export duties, deregulating, privatising and opening up many investment opportunities, we wouldn’t have achieved stability. Unfortunately those ground rules were afterwards reverted, a trend in our country. This has to do with Argentina’s political leadership.

You were Central Bank governor a year after an economy minister who became famous for the phrase: “He who bets on the dollar will lose out,” Lorenzo Sigaut, who created forward exchange cover for dollar debt after José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz and his ‘tablita’ (a sliding scale of pre-set foreign exchange guidelines). Shortly after you left, indeed many accuse you of that too, the new Central Bank governor decided to directly absorb all private debt (then US$17 billion) as public debt, broadly similar to the conversion of that debt into pesos in 2002. It seems that every now and then the Argentine private sector demands the conversion of their unpayable debts into pesos in order to liquidate them. [Former Central Bank governor] Federico Sturzenegger wrote an article in Perfil saying that the inflationary tax thus generated by the government was worth almost two percent of Gross Domestic Product in revenue. How does Argentina break out of that culture?

The idea that debts are finally not going to be paid is what leads to defaults every now and then on the foreign debt or dollars under foreign law – equally a mega-devaluation with inflation rates very much higher than the previous to liquidate debts in pesos is a trend deeply rooted in the culture of all economic operators and also savers, which is why they run away from saving in pesos since they know that they’ll be the ones who finally end up paying the bill.

Going to a good monetary system with interest rates reflecting zero inflation expectations is essential but it has to be understood and accepted by the economic operators. That does not change overnight but only by persevering with the right ground rules. In the last years of convertibility due to the indiscipline of the public sector (basically the provinces) and also the desire of businessmen with dollar debts to unload them via their conversion into pesos and devaluation, we arrived at a climate of opinion, even among the political leadership, which produced the coup of 2001 and the absurd measures taken at the beginning of 2002.

The world economy abandoned the gold standard for good in 1971. If there had been some form of convertibility, we would not have been able to face the subprime crisis of 2008-2009 with “quantitative easing” to avoid a repetition of the 1929-1930 crisis nor now with the pandemic, given the enormous quantity of money printed by the United States. Were the convertibility systems typical of 19th century economics and much of the 20th unsuited to the hedonism of more recent generations or perhaps our grandparents were used to levels of suffering which modern societies would not tolerate?

The gold standard had already been abandoned in the 1930s. Monetary policy was needed to get the banking system going and permit economic growth. In 1971 the United States ceased to declare its currency convertible into gold, a commitment assumed at Bretton Woods at the end of World War II. The request made to other countries was to set their currencies in dollar terms at fixed exchange rates but adjustable under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The US exit from that dollar discipline, combined with all other countries transforming their money into floating currencies against the dollar, is part of the explanation for the inflation in the 1970s which only began to be resolved with the very tough monetary policies of [US Federal Reserve chief] Paul Volcker in 1981-1982, provoking a major recession. Trust was restored in the dollar after Volcker practically eradicated US inflation with a huge monetary squeeze.

In Europe monetary confidence was achieved with the so-called ‘European currency snake’ later converging into the creation of the euro. The possibility of monetary policy via the Central Bank because there is confidence in the currency is something good. It helps to exit situations like the subprime crisis of 2008-2009 or the European crisis of 2010-2012. That does not mean that a country with practically no currency will not have to resort to a convertibility regime for a certain period, not against gold but other currencies which inspire confidence.

Argentines save in dollars as their reserve currencies but North Americans save in shares because they are aware that US inflation does not show the true loss in value with the purchase of monetary assets. Isn’t the underlying idea that central banks, and in the final analysis states, end up somehow betraying confidence, in the case of developed countries in homeopathic doses and in the case of underdeveloped countries apocalyptically because they cannot handle crisis?

There’s something in that but it’s not the essential point. It’s not that people don’t save in dollars in the United States. Savings and investments in financial assets are quoted in dollars. US bonds are a savings instrument for many people and even countries like China – they are denominated in dollars, they’re dollar contracts. Anybody investing in shares or mutual funds has a result depending on the activity of the companies issuing those shares as well as on macroeconomic circumstances. When we say that people in Argentina do not save in pesos, we’re not saying that they prefer to save in shares or bonds.

Financial savings are not made in pesos because they get devalued. It is true that to the degree a country can issue a currency, financing its deficit becomes easier and also true that the monetary debts of those countries are devalued by a reduced annual inflation of two to three percent so that the people of those countries buy bonds if they want to protect themselves against that devaluation. If they have a slightly greater capacity of market analysis, they can buy other shares or invest in mutual funds which give a higher profitability. But the system works well even if there are bubbles every now and then which are dangerous.

Juan Carlos Fábrega has praised Martín Guzmán’s fiscal discipline, saying: “He’s making the biggest squeeze he can but without saying so.” Do you agree?

There has been a fiscal adjustment but it is rooted in inflation and has accelerated inflation. That helped to increase revenue beyond the tax increases, which were a bad policy but still produced results. Like that change in the system for updating pensions, a total miscalculation on the part of the government, which believed that they were thus going to improve pensions when they have actually worsened them in real terms.

The only thing which has been achieved by Guzmán’s fiscal adjustment is that wage increases in the public sector have not been as high as inflation. I do not see any structural adjustment really leading to any permanent reduction of public spending and the fiscal deficit. On the contrary, their initiatives are pointing towards ever more deficit. They talk of nationalising the Hidrovía waterway and possibly the private ports. That cloaks the idea of renationalising everything related to foreign trade logistics and foreign trade itself.

You only have to remember what the ports and the dredging works of the Paraná River were like when done by the Administración General de Puertos and all it cost to advance in privatisation to realise how absurd that approach is. It will imply very bad services, which will burden grain exporters.

In a lecture you gave recently at UCA Catholic University, you said that much of the increase in Argentine exports had to do not only with technological advantages and investment but also with being able to export via the Hidrovía and the improvements in the ports.

In the entire logistical system. Farmers will surely remember that until the reforms if the 1990s, what was paid to transport grain to the ports, what was paid for port services and then the river and maritime transport, all that, together with the inefficiency of the grain elevators and the rest of logístics, was a cost burden for producers, who also had to put up with export duties, thus earning less than half the value of their production on international markets. Much of that was corrected by privatising the ports, the Hidrovía, the grain elevators and the trains, facilitating greater efficiency and less logistical costs. All that ended up in more income for producers, permitting them to incorporate technology and invest, thus expanding agricultural frontiers. The grain harvest rose from 30 million to 130 million tons. All that now falls under a shadow. You only have to listen to the ideologues of these measures like Banco de la Nación director Claudio Lozano or [deputy] Fernanda Vallejos or Senator Jorge Taiana, who now unfortunately heads the Hidrovía system. One can only conclude that they wish to return to the pre-1990 system. That is why farmers are manifesting their opposition, quite rightly. They have not yet made explicit what they have in mind but it is suggested by the stances of those persons. It reveals that we are moving in a very wrong direction.

Comments