At Argentine brokerages and banks, the calls come in every day with the same question: How many dollars does the Central Bank actually have?

Keeping a close eye on international reserves has become a ritual for Argentine investors as they try to figure out what comes next for the peso and US$65 billion of recently restructured overseas debt.

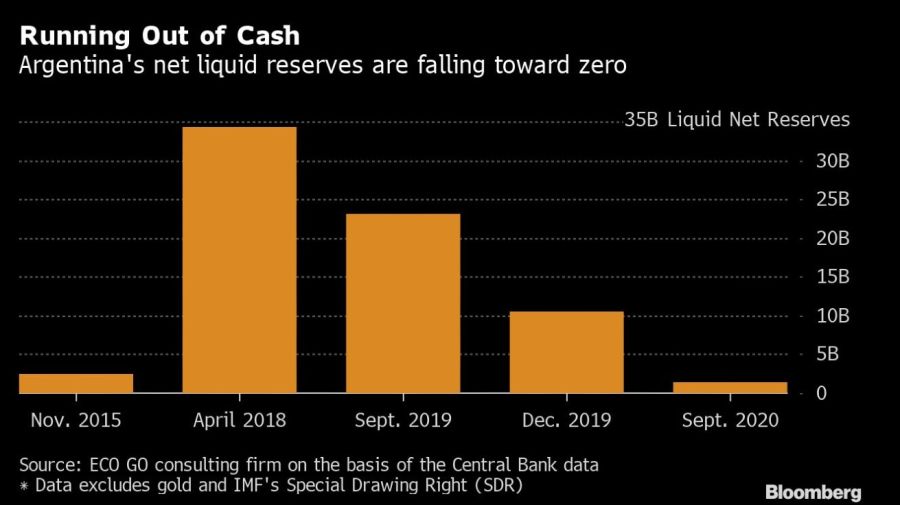

Calculations for the exact amount of net liquid reserves vary from negative US$2 billion to as high as US$1.3 billion depending on how various piles of money are counted, but almost everyone agrees that it’s ominously low. As the balance heads ever lower, the government is piling on measures to stop the bleeding. The latest effort came last week as officials cut taxes on some exports, said they would allow a faster devaluation of the peso and raised a local interest rate in their desperate effort to hold onto dollars.

“I’m getting hammered with questions and calls,” said Juan Manuel Pazos, chief economist at TPCG Valores in Buenos Aires. “What they want to know is our view and how we expect policy makers to respond.”

While Argentina’s Central Bank publishes its total dollar reserves five times a week, investors are most interested in the country’s net liquid reserves, basically what’s available in cash. That figure is just a fraction of the US$41.3 billion gross amount, but arriving at an exact number is tricky. The Central Bank doesn’t tally it on its own and a press official declined to comment on analysts’ estimates.

“The trend is the key,” said Emiliano Anselmi, an economist at Portfolio Personal Inversiones in Buenos Aires. “And the trend shows the reserves keep falling.”

In mid-September, Argentina had tried to limit the drawdown by putting severe restrictions on dollar purchases, both for individuals and companies, but demand for greenbacks showed no signs of slowing. A parallel exchange rate used to skirt controls has fallen to a record, with the peso worth almost half of what it fetches in the official market.

Meanwhile, prices for Argentine bonds issued just a month ago have fallen ever deeper into distressed territory, with most new dollar notes trading at around 40 cents on the dollar.

It’s all a giant vote of no confidence in President Alberto Fernández’s administration just weeks after the country won some US$38 billion of savings in its restructuring with promises of stability to come. Inflation has remained stubbornly above 40 percent, unemployment is at a 16-year high and Argentina’s economy is forecast to shrink 12 percent this year, its worst one-year contraction on record.

Lens on the numbers

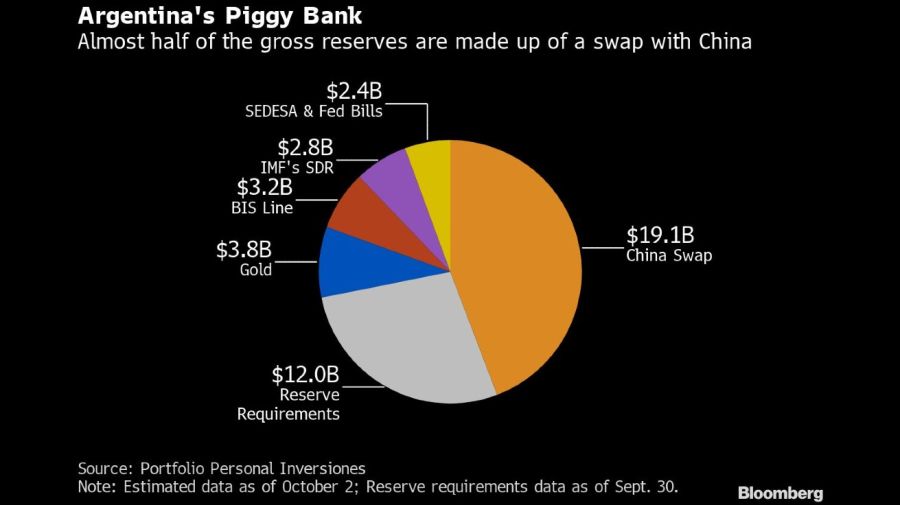

Amid the gloom, investors are focused on international reserves as a key indicator. To calculate how much of its own money the Central Bank has on hand, analysts first subtract US$12 billion of commercial bank deposits from the US$41.2-billion figure for gross international reserves.

Then there are approximately US$25 billion of currency swaps, drawing rights and other lines that aren’t liquid. Some shops also exclude US$2.4 billion from repo operations and US bills. And without the US$3.7 billion of gold bars, net liquid reserves are negative US$2 billion, according to Portfolio Personal Inversiones estimates. That’s a similar number to JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s latest calculations.

But other shops are more generous in calculating reserves. TPCG Valores counts US$200 million of liquid reserves and Eco Go says the total may have been as high as US$1.3 billion as of the end of September.

Almost half the gross reserves amount comes from a 130 billion yuan (US$19.1 billion) currency swap with the People’s Bank of China. It’s been around for more than a decade and was renewed in early August.

The swap line allows Argentina to ask for the money if it needs it, though the PBOC is under no obligation to disburse it, according to Fausto Spotorno, economist and director of the Orlando Ferreres & Asociados consultancy in Buenos Aires.

If the country asks for the money, it will need to start paying interest on the credit line. The same happens if Argentina taps the US$3.2 billion that comes from a line with the Bank of International Settlements.

Argentina also has US$2.8 billion of Special Drawing Rights with the International Monetary Fund, which could probably be converted to cash fairly easily, though the fund’s board would have to approve. Then there’s the gold bars, which would have to be sold or offered as collateral on a loan.

“It would be a really bad sign if the Central Bank sells the gold” because it’s a source of stability, Anselmi said. “It’s like you have nothing left.”

related news

by Jorgelina do Rosario, Bloomberg

Comments