Several biographies have been published on the life of Máxima Zorreguieta, the woman more famously known as Queen Máxima of the Netherlands. But only one of those accounts was chosen as the source material for Máxima, the new streaming series on Max (HBO).

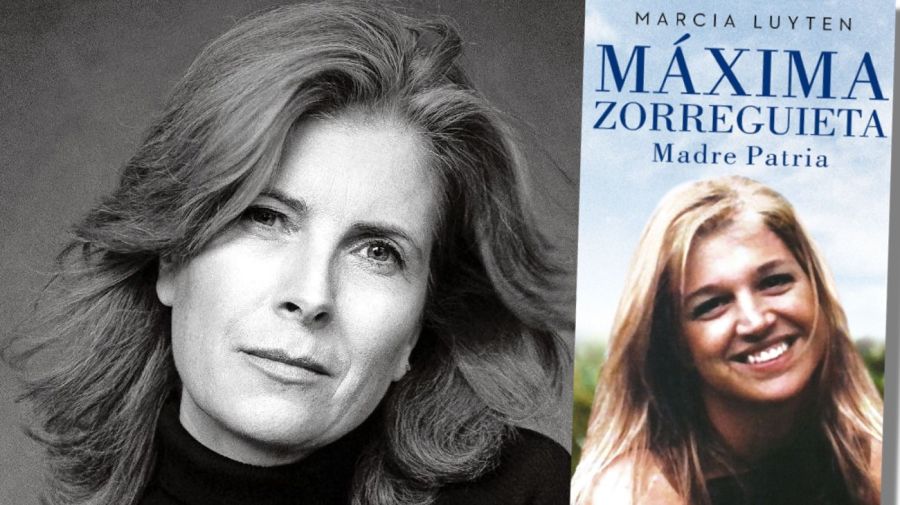

The book in question is Máxima Zorreguieta. Madre Patria, by Dutch author Marcia Luyten. It is the basis for the new series starring Delfina Chaves and Martijn Lakemeier.

Luyten conducted thorough research, delving into the most intimate corners of Máxima’s life, focusing on her childhood and teens in Argentina, and highlighting how her roots and training have profoundly influenced her role within one of the oldest monarchies in Europe.

The author immersed herself in Máxima’s life before fame thanks to a series of 132 interviews with people close to the Queen of the Netherlands. During the research stage, the writer travelled to Argentina on several occasions, discovering details which marked the monarch’s youth.

Máxima Zorreguieta. Madre Patria offers an intimate portrait of Zorreguieta Jnr, from her hectic childhood to her transition into adult life. It highlights the decisive influence of her mother on her education and her extraordinary ability to adapt to the occasion.

It is surprising that Luyten, who trained as an economist, accepted a work so far removed from her first specialty. To many, this arouses the suspicions that, even if it is an “unauthorised” biography, the work may have been assisted or edited by Máxima and her team, under the close supervision of the Royal House of the Netherlands, which is known for meticulous censorship in such matters.

According to the text, Máxima is a woman who has always had the ability to move freely through different social circles, a talent she inherited from her father, Jorge Zorreguieta, who from 1979 to 1981 served two years as agriculture, livestock and fisheries minister in dictator Jorge Rafael Videla's regime.

The book also explores the qualities that have allowed the wife of King Willem-Alexander to successfully blend into the Dutch royal family and win popularity in her new country, despite the political tensions prior to their marriage.

Luyten narrates how a strict education and the high expectations of her family moulded Máxima’s character and prepared her for life. The author covers the moments that marked her personal life, including the controversy surrounding her father’s role in Argentina’s 1976-1983 military dictatorship, and the deep grief she experienced after the death of her younger sister, Inés.

These elements humanise the queen and reveal her resilience in the face of adversity.

Máxima, the new Max series, is directed by Saskia Diesing, together with Joosje Duk and Iván López Núñez, and produced by Millstreet Films, in collaboration with FBO and Beta Film (with controversial support from the Dutch Film Fund Production Incentive, the Creative Europa Media programme and the Belgian Tax Shelter).

Over the course of its first season, it narrates the defining part of Máxima’s early life, from her childhood up until the time she meets Prince Willem-Alexander; a transcontinental romance which started in 1999, when the couple first met at the Feria de Abril de Sevilla.

With all the necessary ingredients to become a hit, in the style of huge streaming productions such as Netflix’s The Crown, the new series promises to draw a large audience, both inside and outside Argentina. Plans are already underway to begin shooting a second season in the coming months.

Interview with author Marcia Luyten

To what extent was the Dutch state involved in research for the book, considering that you visited the estate of the Augspach family in Pergamino with the Dutch ambassador?

I went to Pergamino, to the estate of the Augspach family [NB: Estancia “El Castillo"], to get an idea of what it meant to have one of these estates in Argentina. I visited Pergamino, where I spoke to Máxima’s aunt, Margarita. But I also spent a night at the Augspachs’ ranch.

What also happened is they invited several people, including the ambassador and his wife. We were around 20 people enjoying an asado. When it was over, the ambassador offered to take me to Palermo, and that was it. There were no political favours, no links with the Republic. Even the embassy never wanted anything to do with me.

I interviewed the ambassador, of course, but I’ve always maintained my total independence. That’s why it’s not an authorised biography.

What’s your opinion of Queen Máxima?

I think she’s a fascinating person in the sense that she has a very complex and diverse character, with characteristics that contrast in an opposite way. If we talk about someone with a complex character, we usually think of someone difficult, but she’s quite the opposite. She has a huge ability to adapt and adjust. She’s very pragmatic and, at the same time, extremely emotional and passionate. It’s amazing how such contrasting traits can coexist.

Another characteristic is her chaotic nature. As a girl, she was very chaotic: she would bang against doors, break her fingers, make messes. And yet, she’s also very disciplined and a perfectionist. All these aspects which might seem opposite intertwine and that, in my opinion, makes her so good at what she does.

You noted that Máxima has many commitments. Is she involved in more humane topics, women or the feminist collective? Considering other queens who focus their work on these subjects...

When Máxima arrived in the Netherlands, it was obvious to everyone, even her mother and family, that she had her own career. In New York apparently, she was a success. Then she came to the Netherlands and everyone said: ‘This lady is skilled.’ And I think it was crucial for her to continue developing a career.

Of course not an open career like we might have, because she was going to be the wife of a king. But soon she was requested to be part of a group of advisors in the United Nations about microcredits. In time, she liked it and wished to continue working for the UN. And that led to the creation of a post in a General Secretariat on financial inclusion. First it was about microcredits, but then it was expanded to financial inclusion, which is a much wider field.

Financial inclusion focuses on people by its very nature, especially women, having access to bank accounts and insurance. So a Wall Street economist became a development economist, and she did it in a way that earned much international respect.

How do you think she was received in the Netherlands, initially as a woman who dressed in such a flashy way, so different from her predecessors, from other queens?

Máxima wears designs by Valentino and Natán, her favourite. Many people said: ‘Oh, wow, we finally have someone who knows how to dress with style.’ And she’s beautiful, she dresses elegantly, and shows it off with pride.

She has style, she has grace. So many more people love that more extravagant style. Besides the large capes and imposing rings. She’s more glamorous. Of course there are also those who criticise her, though most people think that her style adds a special value to her function. Sometimes I think she looks great. I don’t have a clear idea about it.

As for her father, who was part of a de facto regime, do you think that subject won’t leave Máxima alone?

The agreement was that Máxima could marry the King, but her father couldn’t attend the wedding, which was, of course, a very painful decision for her and her family. It was a huge sacrifice her father made. I think for an Argentine it is unimaginable not having your father, whom you love so much, at your wedding. They loved each other deeply, and he couldn’t be there. But she made it work. Máxima is very pragmatic, what you see is what you get.

She publicly condemned [Jorge] Videla’s regime in the Netherlands, definitively, and more than once. When their engagement was announced, she was by Willem-Alexander’s side and she issued a brief statement publicly apologising for her father being a part of such a dark regime. So she did it.

She also invited the Madres de Plaza de Mayo to the palace and she met journalists who wrote a book about the dictatorship. However, to some, these actions were not enough to reconcile both parts of history, always casting a shadow on the figure of her father, and by extension on Máxima herself.

What do you see of Argentines in Máxima? How much do you think her role influences culture?

When she arrived in the Netherlands we said to ourselves: ‘Oh, she’s different.’ We started to notice she wore large shoes and sang with the king. She’s a great dancer and singer. She was much more expressive. It was so unlikely for a queen who wasn’t afraid of crying in public. She’s very emotional.

As I said before, that contrasts with her more controlled and pragmatic side. She’s very warm, much warmer than we expected the wife of a king to be. Most people in her position are more reserved, a bit firmer. And then, the way she dressed, much more extravagant. If extravagant is the right word, she’s definitely extravagant!

– TIMES/MARIE CLAIRE

Comments