The 61-year-old business leader, who has close ties to former presidents Néstor and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, turned himself to federal authorities on Thursday after a judge ordered his arrest on charges of fraud and tax evasion.

Hours earlier, his business partner Fabián de Sousa had also been arrested and jailed, while the former chief of the AFIP tax bureau, Ricardo Echegaray, was charged but not arrested.

According to Federal Judge Julián Ercolini, López and de Sousa set up a tax evasion structure that allowed them to forgo some eight billion pesos (some US$450 million) in debt owed to the state. The missing funds come from the ITC gas tax, which relates to their energy company, Oil SA.

The weeks building up to López’s arrest were marked by desperation. The tycoon had engaged in secret negotiations with President Mauricio Macri’s judicial operators in order to find an agreement, according to two sources familiar with the case.

When he failed, the businessman tried to sell off his stake in media companies — first to Orlando “Orly” Terranova, a man who once ran as a candidate for Macri’s political party, and then to Ignacio Rosner, a man who worked for the business group long owned by Franco Macri, the president’s father. But despite his best efforts, López could find no way out of the crisis. Time, it seems, had run out.

FIRST PATAGONIA, THEN DE (GAMBLING) WORLD

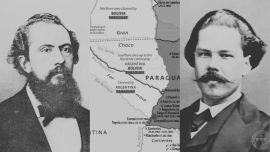

Cristóbal Manuel López was born in 1956 in Buenos Aires, but grew up in Rada Tilly, a dry and windy city in the southern province of Chubut. His parents owned Patagonia’s largest transport and forage company, but both died in a car accident when Cristóbal was only 18. “After my parents died I took over the family business. Working is all I’ve done ever since,” he said in a 2008 interview with Clarín.

In truth, he ran his businesses as a contractor for oil giant YPF and added new ones, most of them as a government contractor.

López’s career as a casino tycoon began in Chubut in the 1990s, when gambling activity regulations were decentralised and transferred to the provinces. Local governments started to promote the industry as a key source of revenue. López’s network of casinos and bingo halls soon expanded to La Pampa, Misiones and Mendoza, as his negotiations with political powers resulted in gaming licences, tax exemptions and other favours.

But his fortunes would improve even more after meeting Néstor Kirchner.

López said the first time he first met the former president was through Julio De Vido, the powerful ex-Planning minister who is now in jail on corruption charges. Kirchner, a Peronist leader from the southern Santa Cruz province, won the presidential elections in 2003, the same year López was awarded three casino licences in Santa Cruz.

By 2007, López had established himself as the country’s pre-eminent gaming mogul, as the head of the Argentine company Casino Club. He purchased a stake in the controversial floating casino of Puerto Madero and partnered with racetrack businessman Federico de Achával to operate 4,500 slot machines at Hipódromo de Palermo (as a comparison, the MGM Grand Casino, Las Vegas’ most popular gaming hall, has 3,700.)

The businessman’s ties with the president were paying off – it was Kirchner who signed a much-criticised decree allowing López to expand his gaming terminals just a week before handing power to his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The decree also extended the business leader’s contract to exploit the Palermo racetrack until 2032. Needless to say, these decisions did not go down well with his immediate competitors.

“He’s not a businessman. He just manages privileges,” one of his rivals in the gambling industry said.

TO THE LIMIT

By the turn of the decade, López was at the top of his political game and, once again, he used his power to expand and push his business interests into other areas. In 2012, his Grupo Indalo company — the management of which has been mostly overseen by De Sousa — bought cable news channel C5N and Radio 10. He followed suit purchasing a number of popular FM stations, including Mega 98.3, Pop 101.5, Vale 97.5 and TKM 103.7, and signing an alliance with popular TV host Marcelo Tinelli.

A multimedia empire was born, perhaps too quickly for an executive with no experience with media outlets.

Expansion continued. Three years later, López’s group purchased a 60-percent stake in Grupo Ámbito, the publisher that owned Ámbito Financiero, the Buenos Aires Herald and the daily El Ciudadano of Rosario. He also bought El Argentino, a free-sheet, and the CN23 cable news channel from Kirchnerite media mogul Sergio Szpolski.

Amid widespread fears of job cuts, Francisco “Paco” Mármol, Grupo Indalo’s institutional director, promised journalists that the purchases was made with the intention of “empowering” those media outlets. But by 2017, less than two years after López’s allies in the Casa Rosada had made way for President Mauricio Macri’s administration, El Ciudadano and the Buenos Aires Herald — a newspaper with 141 years of publishing history — were shut down at very short notice, and dozens of reporters lost their jobs overnight.

It was just the beginning. Grupo Indalo then closed El Argentino and almost CN23. Reporters at Ámbito Financiero began to face lengthy delays in payments of wages. Those laid off at firms across the group saw their severance payments inexplicably cut off.

It was terrible management of a huge media empire: a constant disdain for journalism, with executives yielding to political pressure — and editors, reporters, photographers, designers having to cope with it day after day.

THE FALL

In a wide-ranging interview months with Perfil before his own arrest, De Sousa told journalist Jorge Fontevecchia that the media expansion of the business conglomerate was funded, at least partially, through the money it “saved” by kicking taxes down the road. It was a public acknowledgement of the charges levelled against López and his business partner.

“It could be said that part of the financing we used to pay for Ideas del Sur and (...) Ámbito Financiero [was] the deferment of payment of one our taxes,” said De Sousa.

This “deferment” was, according to Judge Ercolini, an outright fraud orchestrated by López with the consent of the AFIP tax bureau.

The case that brought Cristóbal López down goes as follows: Oil Combustibles, one of the tycoon’s many energy companies, owns 300 petrol stations across the country. By law, 26 percent of all petrol sales are destined for the AFIP. Oetrol stations act as intermediaries to collect the tax.

The judge in charge of investigating the case has said AFIP officials from the Cristina Fernández de Kirchner administration — including its chief, Echegaray — “failed to do things so that those funds were withheld, refinanced or given another purpose, but were not paid to the AFIP.”

López, it seems, read the writing on the wall. Of late, many of his movements have been seen as a flight forward, an awareness of the terrain shifting below his feet. In 2015, Grupo Indalo had become a majority stakeholder in the Finansur Bank, but López later tried to sell it back to a small-sized financing firm called Grupo Fiorito, a move that was ultimately rejected by the Central Bank. This strange manoeuvre was followed by him reportedly moving away from the casinos.

Two unsuccessful attempts to sell his media companies to businessmen close to Mauricio Macri came next, as the group’s workers faced rising uncertainty over their own futures. Like a scene out of The Sopranos or Goodfellas, the race against the clock for this obsessive and ruthless businessman has ended in a federal penitentiary. Cristóbal López, the millionaire who turned billionaire thanks to the favours he received from Kirchnerite politicians, is now behind bars. And he has a lot of explaining to do.

Comments