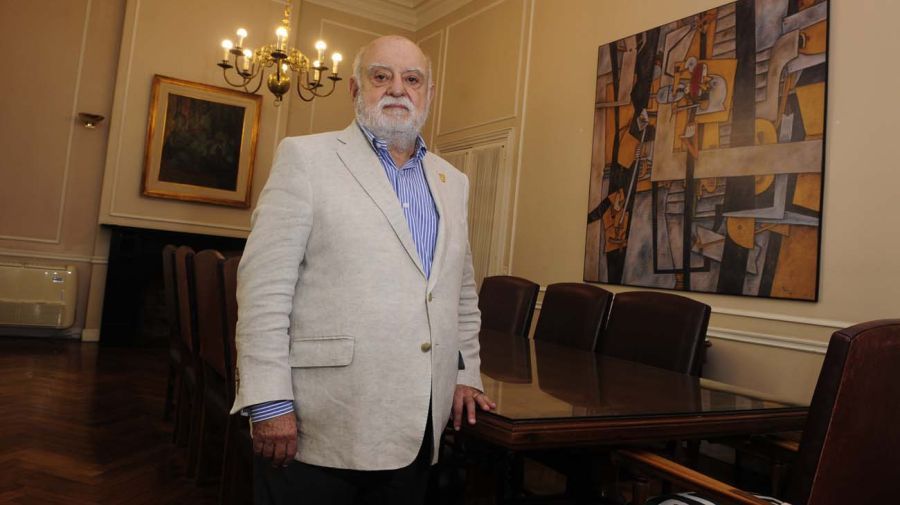

Rodolfo Barra, Argentina’s new Treasury attorney, heads state lawyers as the presidential legal spokesman. At present, the 76-year-old’s main task is to defend the validity of President Javier Milei’s emergency decree DNU (Decreto de Necesidad y Urgencia) 70/2023.

Justice minister and Supreme Court justice within the automatic majority established by ex-president Carlos Menem in the 1990s, Barra’s other posts included Public Works deputy minister, Interior Ministry secretary and head of the board of directors of ORSNA (Organismo Regulador del Sistema Nacional de Aeropuertos) aviation regulatory agency.

His Nazi past during his adolescence, of which he has repented and for which he has apologised, removed him from public life towards the end of the Menem decade.

This unusual interview had to be recorded in three stages over three days – what follows is an extended extract from it.

Legal expert Andrés Rosler, who wrote an article headlined ‘Revolución o Constitución,’ may be quoted as saying: “One of the most consistent defenders of using DNU emergency decrees is the current Treasury prosecutor Rodolfo Barra, who recently maintained that the Constitution refers to exceptional circumstances which do not need to be an earthquake or a pandemic or some natural catastrophe preventing Congress from sessioning but may be decided by the president himself.” I would ask you to go into greater depth with your idea.

That’s what the Constitution says in the third point of Article 99. Only when exceptional circumstances make the normal law-making procedures as defined by this Constitution impossible but those exceptional circumstances can be very different. And the important point is that the ordinary sessions of Congress cannot be awaited to pass laws. The President appreciates this, that the exceptional circumstances are a situation out of the ordinary which does not need to be an emergency situation. We are talking about reasons of need and urgency which are not an emergency nor a declaration of war nor a Martian invasion nor an earthquake devastating the country but an exceptional circumstance such as the one we are currently undergoing which, apart from being urgent and necessary, is, of course, singularly grave, not permitting us to await ordinary sessions.

It is not that Congress cannot meet because Congress can always meet, even in January or February if summoned by the President to approve legislation. No, what cannot be followed is ordinary procedure because that is necessarily slower and more deliberate with the intervention of two appeals courts. There could be three reviews, by the original appeals court, by the appeals court of review and then back to the original appeals court so that takes up quite a bit of time. Congress afterwards evaluates if the President’s appreciation of the situation was reasonable so emergency decrees do not exclude the intervention of Congress – on the contrary, they may provoke it.

The constitutional text is being badly misread. So that people may realise the speed with which we need to act, I’m going to read out to you the third subsection of Article 99 of the Constitution referring to the DNU (decreto de necesidad y urgencia): “The Cabinet Chief will personally submit the measure for the consideration of the Permanent Bicameral Commission within the space of 10 days... This Commission will then present it to the immediate consideration of a plenary session of each House of Congress within the space of 10 days for its express treatment (to produce) a specially sanctioned law.” So far from excluding Congress, this provokes its speedy intervention.

Congress may intervene in two ways: firstly, via the Bicameral Commission with the decree sent to Congress already regulated by law to pass through the Bicameral Commission which may be assumed to be already studying it, and secondly, the ordinary route via the House floor. Note that the government’s so-called ‘Omnibus Law’ has cleared extraordinary sessions so that it may be debated now, including the ratification of Decree 70/2023, which is what we are talking about. Congress has the power to approve it, repeal it totally or partially or amend it totally or partially – right now or tomorrow. The Deputies could debate it in the morning and the Senate in the afternoon and that would be it. Contrary to signifying an exclusion of Congress, this decree provokes its intervention with far greater intensity, which was the idea behind the Constitution of 1994.

The necessity and urgency depends on the political appreciation of the President and also of Congress. In my estimation this should not be a court question but up to now the evaluation of necessity and urgency has entered into jurisprudence. Well, it seems to me that judges cannot make this kind of political evaluation but that is just my opinion – what obviously counts is the opinion of the judges.

You were a delegate at the Constituent Assembly of 1994. The spirit then was the desire to regulate the decrees used for the state reforms in the first presidential term of Menem before 1994. The third subsection of Article 99 of the Constitution says that the government cannot legislate, in any event on pain of being absolutely and irreversibly quashed, only when exceptional circumstances make following the ordinary procedures provided by this Constitution impossible and nor may DNUs cover norms regulating criminal law, taxation, electoral systems or the régime of political parties. If, in your judgement, the courts have no say as to what is necessity and urgency but only the President is so empowered, might we say that the 1994 Constitution gave the president a delegation of powers which did not previously exist as the only instance to decide on necessity and urgency with not even the Supreme Court entitled to an opinion?

Not just him, him and Congress. What I understand is that judges should not deliver an opinion regarding that political evaluation of necessity and urgency nor evaluate the motives for dictating a state of siege or a federal trusteeship in provinces. The courts themselves have said that those reasons are beyond their jurisdiction, the standard which has always been applied. But I still say, and here I’m giving my opinion, that what finally counts is what the courts pronounce – when the Supreme Court speaks, the case is closed and beyond further discussion. But even when the necessity and urgency is assessed in court, I believe that in this concrete case of Decree 70/2023, we are really undergoing an extremely grave situation on the brink of hyperinflation or worse [recontra hiperinflación, sic]. We all know this and live it. The President has already diagnosed the situation of the country and I believe all sectors to be in agreement. I find it somewhat banal to be discussing this really grave situation.

It clearly becomes valid, simply by virtue of being promulgated by the government and will continue valid until both houses of Congress reject it, making it easier than a normal law which requires the approval of both houses of Congress.

Of course it’s easier and faster, that’s what emergency decrees are for when the going gets tough with the ordinary procedure being too slow. In that case there is “dialogue” between the government and Congress. The government sends the bill and Congress can reject it or approve it or say nothing. Normally the latter since 1994 when it comes to DNUs. You might consider, for example, that the [Raúl] Alfonsín presidency changed the currency via emergency decree and it was never approved by Congress unless the de facto approval of subsequent budgets being submitted in australs and being confirmed over time is considered.

Understanding the legal background is important because in the same way a government could legislate while limiting the intervention, another future government might change everything in the opposite direction and that would not permit legal security. The 1994 Constitution permitted the president to produce emergency decrees carrying the force of law with the approval of only one house of Congress when we have both deputies and senators. Laws normally need the approval of both houses.

That’s not so. Firstly, a future government issuing another emergency decree is normal within the system. One law repeals another. Congress may pass one law today and repeal it tomorrow. We can recall how we had a law to guarantee [bank] deposits and dollarisation, etc. and then Congress approved an emergency law to scrap that system. But that does not mean anything is wrong, I’m not criticising, just saying that Congress can pass all the laws it likes, approving and repealing at will. Well, emergency decrees are along similar lines to laws, that’s one point.

The second point is that since DNUs are akin to laws, they do not need approval in either house of Congress but are valid if not annulled by the Bicameral Commission or not repealed if passing through the ordinary procedure for approving laws. Meanwhile they are as valid as any law.

Valid if not rejected by one chamber so that half of Congress is enough.

If not rejected by one of the chambers. If one house of Congress does not vote for a bill, it is not law either. We clearly need the bicameral system.

If not to reject is to approve, doctor, what is your opinion when you find so many prestigious legal experts saying that an emergency decree on this scale would shatter the separation of powers and the republican system of government? Dozens of legal experts and former judges think that way, for example, [Ricardo] Gil Lavedra and [Daniel] Sabsay. Why do you think so many legal experts believe that an emergency decree on this scale was issued in order to arrogate to the government excessive legislative powers beyond the spirit of the Constitution?

Those are the opinions of those legal experts. As Napoleon said, it did not ruin his civil code if half the bibliography said one thing and the other half another. I further believe that it is not a quantitative problem because whether a decree is valid or not does not hinge on the number of issues tackled, whether one law or several is repealed or amended, it does not depend on all that. The Constitution does not set that condition. Furthermore, if there really is an abusive attitude, the Constitution is quite well drafted, not because I participated in that, but note that Article 101 even grants Congress the prerogative of expelling the Cabinet chief. He may be summoned by a motion of censure and finally removed by a special majority but not as in an impeachment where a cause is required but simply due to the dissatisfaction of Congress with his work as the Cabinet chief. And it is the Cabinet chief who has to defend DNUs in Congress, which thus has him in the spotlight. Congress can repeal the DNU and chuck out the Cabinet chief. Why? Because an emergency decree was abusively issued. So that is in no way granting special powers to the President who is separated from the general administration of the country as the Supreme Chief of the nation but not involved in its administration, which is exercised by the Cabinet chief.

The government has been issuing emergency decrees since the 1860s, the 1860s I’m saying, not the 1960s without any regulation. De facto situations arose like Alfonsín with the Austral Plan or Menem with the Bonex Plan, both before 1994. What the Constituent Assembly wanted to do was to regulate it since there were areas which we did not want to see passing along that route and were excluded due to their importance. On the one hand, taxation and criminal law, which respectively affect so much the assets and freedom of people, were made to follow another route. And to that we added the political questions which could lead to the manipulation of the electoral system, regulating them in such a way as to oblige the intervention of Congress. I insist very much on that.

I quote you as saying: “So as not to allow them to look the other way, we jabbed them to define it.”

Exactly. As we saw when I read out the third subsection of Article 99, Congress intervention is required far more rapidly than with a bill sent by the President. For example, the President has sent to extraordinary sessions this famous Omnibus Law, which is now in Congress without any requisite of speedy treatment. Nobody can oblige the deputies to meet tomorrow or the day after or the Senate to do this or that. In contrast, emergency decrees must have the immediate attention of plenary sessions of both houses of Congress, according to the letter of the Constitution. Rather than being bypassed, Congress is being urged to act. The President is telling them: “This measure, which I am already putting into effect, is so urgent that you have to debate it right now.” And if they don’t, what happens? The measure remains valid.

I’d like to go into more depth about the relationship between the President and the Judicial Branch. You were a Supreme Court justice yourself. I will begin by asking you if you think that just as the Supreme Court was expanded in 1990, do you think that the number of justices should be increased and what should be the Supreme Court’s relationship with the Executive Branch, one of conflict, neutral or collaborative.

In terms of numbers, I have always favoured more. Five seems very few to me. I think that nine would be good, perhaps 11 but I believe that we need more justices in the Supreme Court like in the United States and many American countries. We’re the country with the fewest justices but when measured by population, infinitely fewer. That’s one point.

Not when measured by population. The United States has eight times our population so if our Supreme Court has five justices, the US Supreme Court should have 40 [Ed. - The Constitution does not stipulate the number of Supreme Court justices, which is established by Congress but since 1869, there have been up to nine, including the chief justice].

You’re right and I was wrong, I take back what I said but thinking of our country...

Why did you resign from the Supreme Court, such an important post?

To be a Constituent Assembly delegate.

But being a Constituent Assembly delegate lasts a year whereas being a Supreme Court justice is lifelong.

Well, yes, but that was the decision I took. For me it was a great pride to be a Constituent Assembly delegate but I don’t know if I’d do that again today because the Supreme Court is paradise for any man of law. You were also talking about the relationship – that has to be one of collaboration, it cannot be hostile because the Supreme Court has to review the possibility of the laws and decrees being unconstitutional but without letting itself be influenced, which is pretty difficult. And that is a criterion which has always been followed and taught in the [law] faculty, etc. To the degree that a law can be interpreted so that its application does not contradict the Constitution, you have to go along that path. Declaring a law unconstitutional is a last resort and an exceptional situation. You have to be very prudent. The judges must bear in mind that the Congress and the President express the will of the electorate while they themselves only do so very indirectly.

Since in the United States they elect the judges at certain levels being chosen by direct vote, would you advocate that for Argentina?

No, I believe it to be a bad system which greatly conditions the judge. I have seen electoral campaigns in the United States where the judges need funds to be elected – one judge told me: “I need so much.” And I say: “Who’ll be giving it to him?” because a salary is a salary. That does not seem right to me, I believe the system we have to be good.

On your personal web page you publish a series of works seeking to reflect on the difficult equation between liberty and authority and finding the key to a solution in respect for the requirements of distributive justice. I would like you to go into more depth about the balance between liberty and authority.

It has always been a very dynamic and delicate balance because to be free we need the authority to guarantee our liberty. This is an atomistic and scholastic principle which plays above all on the idea of what is called the justice of the common good. The liberals in the American and French Revolutions expressed it otherwise but the substance is the same. Governments exist to guarantee the rights of their peoples but through that guarantee they monopolise power and authority.

Would that have to do with positive and negative freedoms, that to be free it is also necessary that there be positive liberties, a government and state to generate the possibility of developing those liberties?

Perhaps.

So for you the state is important.

The state is important, of course. The final cause of the polis is the common good. Without the state we could not subsist.

In that aspect of the balance between authority and liberty, Article 331 of the controversial Omnibus Law refers to any meeting between more than three people in the public space needing to ask permission and receive authorisation. Doesn’t it seem excessive that three people already have to ask permission?

Only when those three people meet to make a political demonstration. You go to any public park now and you’ll find groups much bigger than three people – perhaps the number might be changed. The important thing is that protest demonstrations should not prevent people from living normal lives, going to work or school or for a walk or whatever, because if not, we live in an eternal chaos which does not help anybody. In normal situations it could be ignored because it would not have so much effect. In situations of crisis like the present, it could be serious because it could lead to permanent pickets, which we have in fact had.

A specific question for the Treasury attorney. You have to defend Argentina in the trial of the YPF nationalisation where the sentence has already been passed: US$16 billion must be paid and is being appealed. What is your analysis of the Burford Capital request to bag the national state’s 26 percent share package plus a loan to be collected from Paraguay for Yacyretá?

I cannot give details because the local lawyers in the United States in charge of our case have recommended that we not make many statements which could irritate the courts up there. Their professional customs could be a bit different from here. The only thing I can tell you is that we are defending this case with great zeal, not because Argentina does not want to honour its commitments, as President [Javier] Milei, who has every wish to comply, has said. We think that the sum of US$16 billion is very exaggerated but that is something to be discussed up there. And that is one consequence of the state putting its paws where they do not belong in expropriating YPF, the shares of Repsol YPF.

Isn’t the United States being abusive, for example in the case of FIFA corruption, just because a certain sum of money had passed through a US bank, to arrogate to itself jurisdiction? Isn’t US$16 billion exceeding several times the value of the company abusive? And in that sense do not sovereign states have the power and authority to reject the court rulings of other countries, even in cases where the courts of that country have been empowered to settle controversies in the contract of the privatisation?

The truth is that there is not even such a clause – there is no transfer of jurisdiction. The US judge is intervening on the basis of a doctrine developed by the Americans themselves which we are discussing. We continue to argue the lack of jurisdiction.

But isn’t the US abusive in continually claiming to be the beacon of the world without participating, for example, in the World Court in The Hague?

We are discussing precisely this question of jurisdiction.

I don’t want to compromise you any further. We are closing this [stage of the] interview and I want to make an acknowledgement. In the 1990s Noticias magazine, published by Editorial Perfil, ran a cover with a photograph of an arm raised in a Nazi salute and you yourself said: “I was a Nazi” when I was 14 ...

That wasn’t me.

Without entering into an argument over if it were you, you recognised: “I was a Nazi”...

It might have been me but it wasn’t. If I’m not mistaken, it was a kid who afterwards became a Montoneros leader but I’m not sure.

But you said: “I had a Nazi past, of which I repent and for which I apologise.” That Noticias cover followed by other media triggered your resignation. I want to thank you doubly, firstly for this interview, due to that cover and its consequences, as well as knowing that we are not taking a very positive view of the government to which you belong. And secondly because it seems to me that having apologised upgrades you. Obviously if a person evolves from 14 years old, when I believe you were the press secretary of Tacuara organisation, and repents, they have no guilt to discharge. Again I value your having apologised and recognised that something was not right with this interview being a demonstration of pluralism which I believe to ennoble you.

Thank you very much and yes, one does commit mistakes in life, especially in adolescence. Adolescents are unsure of themselves and sometimes in order to seek self-assurance, they can screw things up big time. One such thing is what you are mentioning. Look at those kids who have just killed another kid and now there is a second case already, it’s terrible. Thank God, I never went in for violence, I never actually did anything. I was lucky because my guardian angel protected me and my parents kept an eye on me. I gave my Dad and Mum several nasty turns in my adolescence and at school but afterwards I settled down. I’m very grateful to UCA (Universidad Católica Argentina) for straightening me out by showing me that one can be a believer and favour [19th-century despot Juan Manuel de] Rosas or whatever while thinking tolerantly and democratically about the normal lives of everybody else.

So well, that’s it and 60 years later I’m still game to carry on.

—

Doctor, let us pick up from yesterday with the specific issue of the Labour Appeals Court’s suspension of the labour reform included in the DNU sent by Javier Milei, which you have already announced you will appeal. Does that ruling suspend the reforms or send them back?

It suspends them. The Labour Appeals Court resolved an injunction suspending the application of Chapter 4 of Decree 70/2023. All the rest of the DNU is valid and applicable with compulsory compliance. Chapter 4 remains suspended until that question has been definitively resolved. We are technically plaintiffs filing a writ against that appeals court decision following two channels. On the one hand, an extraordinary challenge before the Supreme Court presented to the same labour appeals court for transfer to the CGT, who are our legal opponents, for their answer. In principle the appeals court has to send the challenge if it concedes it, which it surely will because of the nature of the question - this is heading to the Supreme Court for the Supreme Court to resolve. This takes us into February because we are going to accelerate, surely presenting the challenge this afternoon or tomorrow, despite having 10 days since being notified. But the CGT also has 10 days to answer and will surely make full use of them. So between all the comings and goings and notifications, etc., this will surely reach the Supreme Court in February, which is when the Supreme Court will start to analyse the legal action presented by the Province of La Rioja.

But on the other hand we are going to insist on the administrative litigation court interrupting its January holiday to assert its jurisdiction, which in reality it had already done but the labour court did not take note. So we are going to ask them to assert their jurisdiction, request the file, independently of the case before the Supreme Court, and quash the injunction. Injunctions are always provisional measures so that the judge can lift them at any time if there is a change of circumstances, or even quash the appeals court’s decision since it is null and void in reality. Because the Labour Appeals Court made its decision when it had already received the communication that it had lost the jurisdiction because the file had to go to the administrative litigation court and because they did not give us the opportunity to respond because if the measure had been ruled by a first instance judge, they could have done it without listening to the other side, i.e. us. And because I have the possibility with the injunction to go to the appeals court and give them all my arguments but the appeals court ruled the injunction directly without us having any opportunity to express ourselves.

Furthermore, as I said, the appeals court has no jurisdiction and besides there is really no immediate grievance because the question continues to revolve around whether or not there is necessity and urgency. So the appeals court says: “There is no necessity or urgency which justifies amendments to the system ordering labour law.” And I believe that there is necessity and urgency with a monthly inflation of 25 to 30 percent. That is beyond argument, we are in very grave times, we had already talked about that. And evidently these labour amendments have something to do precisely with reordering the economy because what we want to do is to foment job offers.

And how do you do that? On the one hand, with a series of measures which encourage investment in the expansion of companies and the installation of new firms but for that we have to tell those investors: your labour costs will be reasonable, not a crazy anchor sinking everything. There are many expenditures making up the labour cost, which first the company and then the consumer end up paying and which make no sense. For example, the union contribution which even workers not belonging to the trade union have to pay in order to negotiate collective wage bargaining agreements. We think that has to be voluntary. It is paid by the workers who then go claiming it in their wages from their employers who then go claiming it in the price of the product so that in the end the consumers end up paying, as well as the workers themselves.

Doctor, was the government hoping that the labour appeals court judges would turn over the case to the Administrative Litigation Court, as requested by Labour Appeals Court prosecutor Juan Manuel Domínguez?

We were confident that yes, that the Labour Appeals Court was going to abide rigorously by the law but we also knew that it was a court very heavily inclined in favour of the trade unions and that it was going to be diffícult for them to accede and that is what occurred unfortunately. There is every possibility of this being corrected sooner or later and I believe that it will be sooner. These are alternatives which occur in all court cases and we must not worry too much either.

You said: “I believe that this will be resolved within a week” but if I’m not mistaken, this would remain suspended until February when the court holiday ends and judicial activity resumes. So how does that work?

If we manage to interrupt the holiday in the Administrative Litigation Court, there is a possibility of this being resolved rapidly. There will be more delay with the Supreme Court, which did not interrupt its holiday to deal with the question of San Luis Province, and I don’t think it will do so for this either, because it will surely be reviewing everything together.

Doctor, from your own perspective, will this be decided by Congress or the Supreme Court?

The DNU is already in Congress for debate by the two channels which I think we talked about before – one being the government sending the decree to the Bicameral Commission via the Cabinet chief and the other being the usual Congress procedure because the famous Omnibus law has an article to clear the approval of DNU 70/2023 so that can already be debated and perhaps confirmed by a law. That is another reason why we question the validity of the decision of the Labour Appeals Court, which is meddling in the legislative discussion without respecting the times to discuss laws.

Federal Administrative Litigation judge Enrique Lavié Pico recently decided to break the January court holiday to work on the protective lawsuits against the DNU, and not only in the framework of the labour reforms. Furthermore, he sub-divided the class action presented by the Observatorio de Derecho de la Ciudad. What is your opinion of this ruling. Did you expect it? What measures will be taken? And how do you imagine it will proceed?

In practical terms it is a bad ruling with bad consequences because it will lead to these amparo lawsuits – let us remind people that amparos are lawsuits for rapid protection – being scattered all over the place. Today there are almost 50 of them and there will be 100 in a short while. Afterwards we can talk about what this multiplication will produce. Of those 50 lawsuits, 99 percent are from NGOs raising general questions normally revolving around the absence of any necessity or urgency. In order to avoid this multiplication, explosion, of cases around the same thing which could cause difficulties for the defence, while the state is prepared to act nationwide, it can obviously defend itself much more effectively if everything is concentrated in one place. But also so that there are no contradictory sentences because with 50 lawsuits, there could be 50 different sentences and that would be a scandal. With this in mind the Supreme Court has designed a system whereby the first judge to hear a case of this type inscribes it in a register which the Supreme Court then picks up and concentrates all the lawsuits there, whether from Tierra del Fuego, Salta, Buenos Aires Province (where there are many), the City, etc. This had been decided, with sound criteria in my opinion, by the judge [Esteban] Furnari but the holiday judge Lavié Pico understood it otherwise. He says that there is no uniformity in these homogeneous claims, unpicking the package which had been made in Furnari’s courtroom as the holiday judge. So there is again an explosión. Against that we are appealing to the [Federal] Appeals Court and, of course, we are confident in success. And if not, it will not be all that serious but we will simply find the procedural action a bit more difficult but we’ll get on with it all the same. And I believe that bit by bit the decree is being consolidated, it is already receiving legislative discussion and the Supreme Court is also cognisant. We will see what the Supreme Court decides as from February 1 so that for now we have to run through the alternative procedures. And with respect to what the Labour Appeals Court decided over the lawsuit promoted by the CGT, which suspends the application of Chapter 4 or only labour issues, we are reiterating something we had already mentioned beforehand - presenting an extraordinary challenge to the Supreme Court against the appeals court decision which can only go to the Supreme Court. There is a constitutionally evident question here. If the Supreme Court picks it up, it will undoubtedly be linked to the La Rioja case, which originated there. The Supreme Court will make joint decisions but may well act with greater speed and immediacy in the case of the injunction.

Doctor, in a previous interview I read that you were not very much in agreement with the DNU route. Today in retrospect, was advancing with a DNU the best decision?

It’s not that I was in disagreement with DNUs, there are some very urgent measures which need to be taken. It might have been debatable whether there should have been a single decree or several. Several decrees according to the issue but one single strategy thinking only of the most rapid Congress approval possible, which is what is happening now, but it is not that I disagreed with DNUs.

So you were then in disagreement with one single decree, you would have preferred it to be divided up.

Yes, but it cannot be called disagreement, it seemed more convenient to me. It was an opinión, a question of strategy. The important thing is the content.

Production: Melody Acosta Rizza & Sol Bacigalupo.

Comments