Alberto Fernández grabs a piece of paper and a pen, scribbling down 10 numbers, which he passes to the man opposite him, who does not even speak Spanish.

“This is my personal mobile. Call me whenever you want, any time of night or day,” says the president, via a translator.

China’s Ambassador Zou Xiaoli, with diplomatic courtesy, thanks him for the gesture and reminds him that his leader, perhaps the most powerful politician on the planet, is waiting to receive him on the other side of the ocean, whenever he can make the crossing.

Smiles all around. Then smiles again for the photo, as the other officials present at the important meeting at the Olivos presidential residence – Gustavo Beliz, Eduardo “Wado” De Pedro, Eduardo Valdés and Sabino Vaca Narvaja – gather around.

The meeting, arranged to discuss business and the pandemic that was then hitting the Asian giant, was held on March 17. Just three days later, the president placed Argentina under quarantine. Chinese aid would prove to be indispensable in tackling the coronavirus crisis.

Two weeks later, for the first time in Argentina’s history, China became the country’s leading trade partner, a position it has maintained until now.

Argentina’s growing political and commercial relationship with China added a new and controversial chapter at the end of July, a possible agreement to boost pork exports which has sparked a debate with great impact within the Cabinet, lining up Foreign Minister Felipe Solá against his Environment colleague Juan Cabandié.

A deal, which will more than likely be sealed in the more than possible presidential visit to China later this year, is barely the tip of the iceberg for the extremely close links between the two nations – for example, 85 percent of meat exports depend on China, as does 63 percent of the total hard currency earned by foreign trade and 45 percent of Central Bank reserves.

Argentina’s relationship with China today is so close that it is quite literally heading into the stratosphere – the first time a national flag was flaunted in outer space was in May on a satellite launched by the Asian giant. Manuel Belgrano never would have imagined it. Not so much Argentina, as ArgenChina.

Strategy

In 2004, following long negotiations, Néstor Kirchner communicated to the country that “Argentina has concluded the most important trade mission in all its history.”

He was talking about the agreement which he had just clinched with Beijing, which converted the country into the “strategic trade ally” of the Asian giant.

That political and commercial pact, the first in the long history of the relationship with China (which began with a mysterious trip by Isabel Perón and José López Rega to Pekíng in 1973, 10 days before Héctor Cámpora became president), made material an undeniable reality – by the end of 2003 Argentine exports to that country were setting a record of US$2.44 billion, thus quadrupling the volume a decade previously.

One of the brains behind that agreement had been the then-Cabinet chief. Back in 2004, Alberto Fernández was not only oiling the wheels, he was flexing his political skills with long months of meetings. His mission: to convince most of the círculo rojo establishment that China would be investing US$20 billion in Argentina, which became one of the central news items of that year. It was no trifling sum – almost half of what the country today owes the International Monetary Fund today. Although that money never arrived, this anticipated the importance which the official gave China, something which began to become more concrete once he became president.

Alberto Fernández has done much more than just leave his personal telephone number with the Chinese ambassador. In less than nine months he has exchanged five direct letters with his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, beginning in February. At that time the Covid-19 outbreak was a reality affecting China almost exclusively, while several powers were minimising the impact of the virus or even suggesting Oriental malice. Fernández was the first Latin American leader to send his “support” to his Chinese colleague. The president, however, was just getting warmed up.

Covid colleagues

Since the arrival of the pandemic, China has sent over 35 flights under the framework of “Operation Shanghai,” as it has been baptised by the Buenos Aires provincial government of Axel Kicillof, and three ships with medical equipment for Argentina.

Just from the aircraft, it is calculated that by the time all the scheduled flights have completed, China will have delivered almost six million face-masks, 83,000 goggles, 700,000 facial shields and 12 million pairs of disposable gloves, which will cost Argentina almost US$60 million – below the market price and with faster delivery.

The question is inevitable: Could the country have successfully faced up to the pandemic crisis without Chinese aid? And to that question should be added another, one which from the beginning of time has tormented the less developed states in their relationship with the great powers: what will they ask for, or demand, in return?

For Environment and Sustainable Development Minister Juan Cabandié and for many environmental activists, including the lawyer Enrique Viale, that question has already been in part answered: they will require Argentina to take charge of a phenomenal production of pork since China can no longer supply its impressive domestic market of over 1.4 billion inhabitants, almost 20 percent of the total world population. Since 2018, the country has been suffering an outbreak of African swine fever, which has killed off over a quarter billion of its pigs. In July the Foreign Ministry issued a communiqué pointing to a possible agreement (almost concluded by now), adding that “Argentina could sell up to nine million tons of quality pork.” This set alarm bells ringing in environmentalist circles, which assured that pigs on that scale would carry sanitary risks such as diseases or even new epidemics, while destroying the environment and turning the country into an Asian factory.

“China is not doing this to diversify its investments but because it cannot do it in its own country and wants to transfer its risks. No country in the world has achieved socio-economic welfare via overexploitation. With 24 million hectares planted with soy, with fracking in Vaca Muerta and with mega-mining in the Andes, we have half our children impoverished and this is more of the same, the new El Dorado which never arrives,” argues Viale.

That group is joined by Cabandié, a man who helped to bring the president and his veep, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, together.

“This agreement places us on alert, we have to evaluate it well from an integral perspective – in order to gain something in the short term, we could bring about serious problems in the medium,” said the minister during an interview with Radio Rivadavia.

The comments annoyed the Foreign Ministry. “He’s irresponsible, we’re about to clinch an agreement which will bring in US$4 billion and formal employment and he blurts out these statements without knowing anything about the subject,” sources close to Solá say, asserting that the environmental risk is practically nil.

Cabandié’s declarations also irritated the Argentine Embassy in China, headed by Luis María Kreckler, who is seconded by Sabino Vaca Narvaja.

The latter name adds a note of colour revealing the importance of China for President Fernández. Vaca Narvaja, the heir of a political family and a specialist in Asian questions, has written several books on the subject and headed a seminar at the University of Lanús. He was the second diplomat to leave the country in the midst of the pandemic in order to take up his post (the first was the president’s close friend, Jorge Argüello, in order to start work as ambassador to the United States). The conclusions speak for themselves.

Silk Road

One of those who knows China best is the previous government’s ambassador to that country, Diego Guelar, who kicked off the pork agreement.

“We have access to an extraordinary market, a relationship which is very important and which I would like to keep growing. Today China is our main partner as an investor, a banker and a trade market,” he explains.

Guelar gives details of the importance of this link – he tells that when he arrived at the Embassy there were nine Argentine meat-packing plants exporting to China and now there are 95, with Argentina turning into Asia’s main meat supplier. Blueberries, cherries, honey, peas, grapes and horses are also exported there, while on August 8 the first cargo of oranges arrived.

Sergio Spadone, who lived 14 years in Beijing and today is one of the businessmen running the Sino-Argentine Chamber of Commerce, agrees: “An agreement with China suits Argentina more than with the European Union, we’re natural partners with complementary markets.” The Zooms organised during quarantine for the círculo rojo business establishment prove that interest – for the last one on August 4, almost 100 businessmen tuned in to analyse trade ties with China.

There’s also an advance in investment – ICBC and the Bank of China are installed in Argentina, together with Cofco, China’s biggest food company which has an important plant in Rosario and which has already become our country’s biggest grain exporter. Furthermore, the Chinese oil company SINOPEC is now second only to YPF within the sector while the continent’s biggest solar plant in Jujuy was built by Power China.

The two hydroelectric dams in Santa Cruz are also the work of Chinese investment. One of them is named “Néstor Kirchner,” in honour of the agreement sealed in 2004. This also denotes the importance of China not only for national governments but also for various provinces which depend on the financing and employment generated by that country. The next dam financed by China might well be named “Cristina Kirchner” because it was during her government in 2014 that Argentina notched up a further category in its relationship with the Asian giant to become an “integral strategic partner.” This means, as explained by the specialist Jorge Malena in his book ¿Por qué China?, that the bilateral relationship now not only covers political and economic aspects but also cultural, sporting, scientific and military.

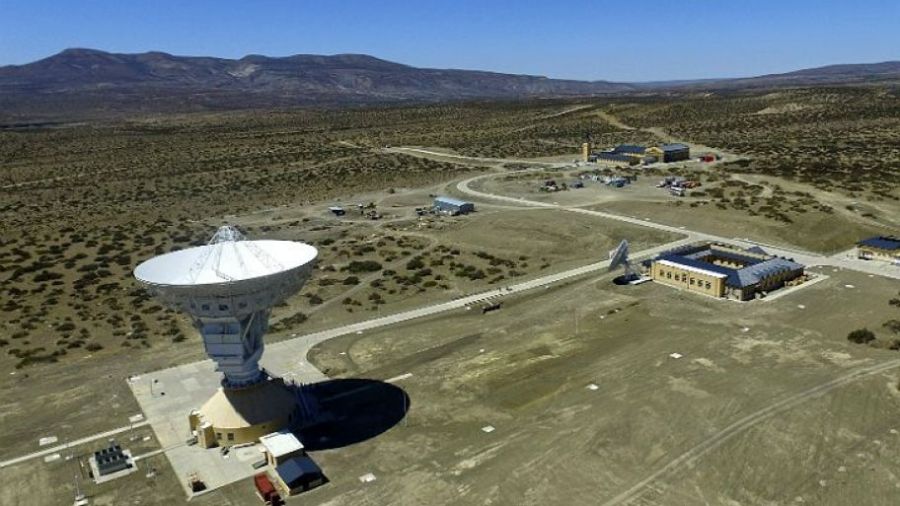

To that last element should be added a controversial project. In that same year Fernández de Kirchner “leased” 200 hectares in Neuquén for 50 years in exchange for a US$300-million investment to build a space observatory. There would not have been so much discussion if it had not been for the fact that this business deal (unlike all the others which just set the main conditions) was directly between Argentina and China, also including the latter’s Armed Forces in particular. That fed suspicions despite assurances that it is only an “outer space observatory” which China considers key to its ambitious project for sending the first human being (obviously Chinese) to the dark side of the moon in 2040. Indeed, as “thanks” for this agreement, the Alberto Fernández government ratified in the Official Gazette of August 8 that the Chinese satellite carried the Argentine flag into space.

History repeats itself. Fernández de Kirchner, who heads the Senate in her role as vice-president, must now take charge of a Chinese issue with the approval of the creation of a Chinese Cultural Centre up before the Upper House as from August 13, a good way of warming up. Next comes the bill to associate Argentina with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the continent’s equivalent of the World Bank.

This is an issue which the president follows closely – with a potential trip to the Asian country in November, he will have to conclude that agreement if the Senate approves it.

Perhaps he will bring back Xi Jinping’s personal telephone number from China with him. It’s the most important one an Argentine president could have, it would seem.

related news

Trial into Diego Maradona’s death given start date: April 14

Silent deputies – the lawmakers who said nothing (or nearly nothing) in Congress last year

Argentina urged to march with photos of disappeared on 50th anniversary of coup

Comments