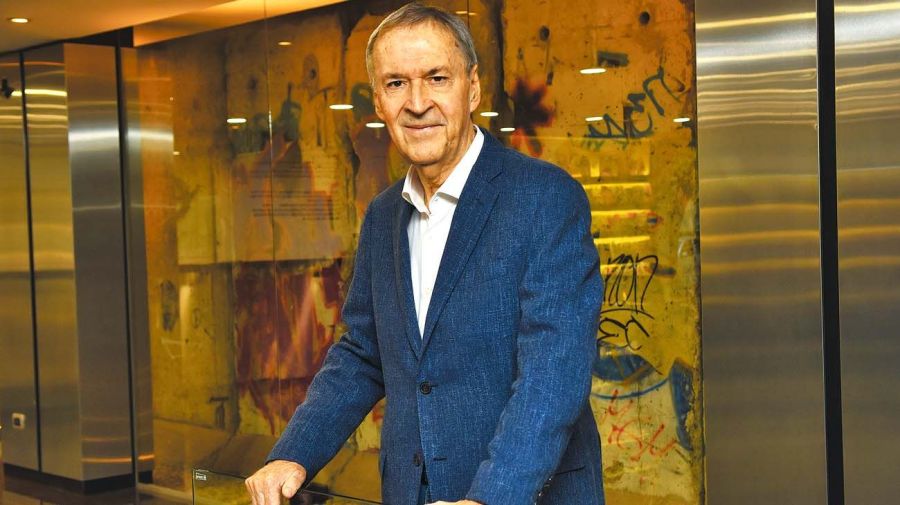

Three-term Córdoba Province Governor Juan Schiaretti is assembling a new political grouping to transcend the grieta chasm.

For the 73-year-old, overcoming polarisation is a fundamental condition if Argentina is to overcome years of decadence and change its productive mix.

What is the impact of the drought in Córdoba and how do you view its economic consequences, not only for agriculture since, for example, only half the trucks are transporting farm produce, apart from all the other spillovers, not simply exports?

In Córdoba it is hitting very hard since we're an agricultural province with that sector carrying almost double the weight in the gross provincial product, as in the gross national product, to give an idea of the importance of farming in our province. That’s why we look after it permanently and defend it tooth and nail. Our agriculture minister works with the Mesa de Enlace [farming lobby group], extending the emergency zone beyond the current area of over four million hectares and adopting measures to aid farmers, that’s the reality. And that is doubtless felt in all connected activities because Córdoba has a total of 427 municipalities and many of them depend absolutely on farming.

When agriculture does well, Córdoba does well and when it runs into difficult situations, that undoubtedly has its impact on all the cities in what we call the “pampa gringa,” whose agricultural frontier has expanded northwards beyond to reach most of the province’s hinterland. And in national terms there is no final estimate of how many billions of dollars Argentina will be losing. They started off thinking it could be US$15 billion, then US$20 billion and now more with consequences for the economy beyond any doubt. But it seems to me that this makes clearer than ever just how wrong the Argentine state’s tax policies towards agriculture are, the export duties which do not exist anywhere else in Latin America, not in Uruguay, Paraguay or Brazil, nor in Europe or Asia, penalising production. And now that the drought has made dramatically evident just how bad such taxation is, it must be gradually lowered until it is eliminated and replaced with income tax.

What we are underlining from Córdoba are the difficulties the drought is causing the farming sector with the lack of dollars suffered by Argentina having an impact on its economic development, knocking two or three points off the gross domestic product.

Every major drought has resulted in exchange rate chaos, the previous one marked the beginning of the end for [former president Mauricio] Macri but there are ways of reducing that risk. In Brazil half the farmland has artificial irrigation and in Argentina only 15 percent. Could irrigation solve these growing problems from climate change?

Firstly, the issue of export duties must be resolved because no other country in Latin America has them. That is key to boosting production instead of punishing it because if this Kirchnerite government has one characteristic, it is treating farmers as their enemy instead of taking care of them as one of the most dynamic sectors of the economy par excellence which can bring in hard currency. That seems to me the first thing Argentina must change.

You met up with fellow-governors Omar Perotti [Santa Fe] and [Gustavo] Bordet of Entre Ríos to celebrate 25 years of the Región Centro, from which emerged a statement calling for, among other things, the gradual reduction of export duties for all the agricultural sector. Should you become president of Argentina, how would you solve [the problem of] the fiscal deficit while lowering export duties at the same time?

Because export duties are a bad tax and Argentina has a number of taxes which penalise production while not collecting the taxes applying to everybody, it’s very simple. We have to simplify the tax system and collect the revenues instead of having the level of evasion there is in this country so that those who do pay end up paying a whole lot with an enormous tax burden. It seems to me that the attack on Argentina’s tax mess lies there.

As for fiscal balance, this should not entail extreme austerity but simply avoiding overlaps between the national, provincial and municipal levels of government while ensuring that energy subsidies go to those who need them. I’m middle-class myself, I don’t need my energy subsidised. It’s also all about state companies not running up deficits – I’m not going to enter into any ideological discussion as to whether [the ownership of] any company should be public or private, all I’m saying is that the company should not run a deficit. In Córdoba we have a provincial energy utility which is publicly owned and pays tax on its profits because it has them. Ditto for the Provincial Bank of Córdoba. There is thus no motive for any state company to run a deficit. If something needs subsidising, that should come from the Treasury for those who need them.

Tackling those three aspects, Argentina’s fiscal deficit can be resolved without any need to attack the vulnerable sectors because the causes which I mentioned recently are the reasons why the fiscal deficit is so big while at the other end simplifying taxation and removing taxes which distort and penalise production.

The statement from that meeting highlights that the central region represents 25 percent of Argentina’s gross domestic product and 38 percent of exports whereas Buenos Aires Province has 32 percent of GDP rising to a half if you throw in the City of Buenos Aires. Part of Argentina’s problem is centralisation around Buenos Aires City and Province because when comparing Córdoba, Santa Fe and Entre Ríos, the three of them together still have a smaller output than Buenos Aires Province.

I would say that rather than with all of Buenos Aires Province, the asymmetry is with that vast metropolitan area of Buenos Aires [AMBA, in its Spanish acronym], where things are centralised. The Buenos Aires Province hinterland has the same characteristics as this country’s central region, that seems to me the most pending issue. One of Argentina’s problems is that ever since we were born as a nation with a federalism proclaimed in the Constitution, we have functioned in a unitarian way as a country.

Would you say that the Córdoba businessman resembles the Brazilian businessman?

Yes, much alike. We work together with the business world and the style of governance we have in Córdoba is to respect the institutions while nobody interferes with the judicial system. Of our seven provincial supreme court justices, three have been there for more than 25 years and nobody ever had the idea of impeaching them. Secondly, the Council of Magistrates is not run by politicians, the judicial branch of government has the majority there. Thirdly, all the posts of that judicial branch, whether prosecutors or judges, are filled by competitive examination. In fourth place, both my friend [previous Peronist governor] José Manuel de la Sota and myself refrained from changing the order of merit so there is a separation of independent powers, we do not persecute anybody, there is freedom of press and tolerance for those who think differently, which also creates the conditions for making the province predictable. That creates confidence and subsequently the certainty of maintaining fiscal balance over time without entering into vain ideological discussions over “this has to be state, this has to be private or the state must regulate many things.”

This Región Centro has its geographic logic but does it mean something more – an attempt to construct a non-Kirchnerite pan-Peronism?

The Región Centro is an expression of production and labour for that is what our three provinces stand out as desiring. We in Córdoba believe that Argentina needs a government which rotates around those who toil and produce, those who get up every day in the morning to go to work – that’s what our central region expresses. Something inserted in the DNA of those three provinces, over and above their circumstantial governors.

And what we also express is that we want a normal country. We must not go lurching from one side of the road to the other or fighting cats and dogs. Over 10 years ago Kirchnerismo invented this grieta chasm and Cambiemos fell into that grieta trap which is now making political leaders fight like cats and dogs outside what is going on in society. They go rotating within their own little orbits, forgetting people’s problems.

When you say to me: “You do not appear much in interviews,” I do not indeed appear because I have to dedicate myself to resolving the problems of Córdoba rather than to commenting on reality and far less to getting into cat-fights with other political leaders because dedicating yourself to resolving people’s problems should be what it’s all about. This grieta is calling for that and that’s why new phenomena are appearing like [Javier] Milei, who is expressing the legitimate rage of society with Argentina’s political leadership. I hope that we can come out of this grieta and the way out is like in labyrinths, by moving up. That is why we are pushing a grouping which is not only Peronist but also expresses the culture of production and work seeking a normal country which not only Peronists may join but also those of other political parties. In fact we are constructing this grouping along with the Socialists and the Christian Democrats while entering into conversations with other political forces.

Now concerning Peronism, we have to free it from the colonisation inflicted on it by 20 years of Kirchnerism. What is worse, Kirchnerism has governed during 16 [of these 20] years but when you look at the results for Argentine society, we are worse off. Per capita GDP is lower now than it was in 2011 and Kirchnerism has governed in eight of those last 12 years. The practical results of so many years of Kirchnerite government are more poverty, more unemployment and more precarious jobs. They can try to disguise that with pseudo-progressive slogans but the only truth is this reality. That’s why I believe that Peronism has to shed Kirchnerism, because, as we ourselves express in tandem with other forces, nobody has the exclusive right to express production and work.

There are other governors – Perotti, Sergio Uñac in San Juan and also [Alberto] Rodríguez Saá [of San Luis] – and a series of Peronist political leaders who are not Kirchnerites and who seek the same things as you, Senator María Eugenia Catalfamo (San Luis) and the Unidad Federal caucus to which your wife Alejandra Vigo also belongs.

Yes and when you talk to them individually, I’d say that the overwhelming majority of Peronist governors, and also Radical and other governors, think the same. It shouldn’t be me telling them when or how to verbalise it but I’d say the overwhelming majority think that way.

Are the conditions different from 2019 when you did not dare to head what we call the third way, the frustrated alternative of the middle road?

It’s not that I did not dare to lead, it’s that I could not, and never will, say to my people: “Vote for me” and then within a fortnight tell them: “Well, thanks, lads, but now I’m going to try my luck in a national adventure,” that would not be authentic on my part. Nor does that seem to me to be fair on those Córdoba voters who had given me a percentage of 58 percent, the highest for a governor in the history of Córdoba. I could not tell the people of Córdoba that I would be going in two weeks. And everybody in Alternativa Federal knew that as the candidate for Córdoba I could not be a presidential candidate because I could not do that to the people of Córdoba, fail them in that way. I did participate in boosting the assembly of that alternative and if afterwards it did not work, the presidential hopefuls should do the explaining rather than me.

In 2019 those presidential hopefuls included [Roberto] Lavagna as well as Sergio Massa and [Miguel Ángel] Pichetto, today in Frente de Todos and Juntos por el Cambio respectively. Today without Lavagna or Sergio Massa there is nobody else with your credentials to be the presidential candidate for that sector. Have you decided to be that presidential candidate, committed body and soul?

We’ll fight it to the finish but we are going to contest the PASO primaries where there are various leaders who can participate.

[Former Salta governor Juan Manuel] Urtubey, for example.

[Ex-minister Florencio] Randazzo can participate in the PASO primaries as a presidential hopeful, as can Alberto Rodríguez Saá. Other leaders joining up can also participate because that is going to give them substance. It does not seem to me that having several leaders weakens the force, on the contrary, it boosts us, I think. I’ll be going to where our grouping indicates that I ought to be and we’re going to take it to the finish.

Does taking it to the finish imply your being a candidate too?

Taking it to the finish means just that and I’m going to be where I’m needed.

Your wife and senator for Córdoba Alejandro Vigo was a protagonist in the formation of a new caucus, Unión Federal. What is the impact of the new caucus, will both Kirchnerism and Juntos por el Cambio now be obliged to negotiate to make the Senate function more dynamically?

It undoubtedly redrew the political map of the Senate. And I’d like to explain that it has nothing to do with my possible candidacy but has everything to do with safeguarding federalism. And yes, Frente de Todos and Cambiemos will indeed be obliged to negotiate more. Over and above the difficulties in the session, there are issues which this caucus is raising, issues which this caucus never ended up discussing, such as transport subsidies and electric energy, issues related to federalism in our country.

Polarisation is not only an Argentine phenomenon if you look at the United States, for example, or at Brazil where [Jair] Bolsonaro seemed overwhelmed by his mishandling of the pandemic but ended up pulling 49 percent of the vote in the runoff whereas somebody of Lula’s stature only polled 1.5 percent more. To what do you attribute that polarisation, do you think that it’s coming to an end and that a message transcending the grieta chasm is more possible today than four years ago?

It’s possible that the polarisation has to do with modern times and the confusion of humanity when the modes of production change so that now with the scientific and technological revolution underway, this is being produced. The appearance of transitory phenomena of polarisation is always possible in the course of history. That is undoubtedly a worldwide phenomenon but serves to win elections, not to govern, as evidently proved by both Bolsonaro and [Donald] Trump losing. So as it is evident to us Argentines, that this polarisation does not serve to govern, we have to put it to one side. Perhaps it is more comfortable to come out shouting at and insulting the others. But the truth is that for the country to progress and leave behind so many years of decadence so that we can give our people jobs and improve, we need to put polarisation behind us. That corresponds to what those of us who want production, work and a normal country are saying.

You have a positive image of 55 points in Córdoba, something which almost no governing leader can rival, and I would like to know how the libertarian advance is unfolding in a province where those governed are in tune with those governing them. Is the Milei phenomenon different in Córdoba from the rest of the country?

I don’t know how different it will be but I’m not giving anything away if I comment on it. When you look at the opinion polls for presidential voting intentions in the province of Córdoba, perhaps because I’m the governor and because the people of Córdoba are generous to me, I appear in first place but Milei comes second in any opinion poll. I won’t enter into any value judgements as to his ideological position, that does not correspond to me, but I do believe that Milei essentially expresses the divorce between the political leadership and the people.

I’m just a circumstance in the life of Córdoba, the only thing we try to do as a government is to coordinate the creative energy of its people, taking care that they can work and progress. Undoubtedly somebody is going to come along to capitalise on that divorce between politics and the people and Milei fundamentally expresses that, the popular rage against politicians. But it also seems to me if a movement proposing things like jobs, production and a normal country comes along, it seems to me that some of what people find lacking in politics will be transferred to them.

Do you imagine a scenario with four important forces, or even five because the left is growing and reaching 10 percent of the total voting intentions in some places: Juntos por el Cambio, Frente de Todos, the sector you represent and the libertarians, a scenario similar to 2003, for example?

In political terms it is a similar scenario to 2003 but what we have today are the PASO primaries which make more compact the political and social thinking of the various viewpoints of the Argentine people. Perhaps it will not be possible to express but I have no doubt that in social terms, it will be an election similar to 2003.

Production: Melody Acosta Rizza & Sol Bacigalupo.

Comments