Latin America, the traditional poster child for political risk in financial markets, is back as a concern for investors.

Chilean President Sebastian Piñera on Saturday became the second leader this month to declare a state of emergency. The decision came in response to violent protests in South America’s wealthiest country after an increase in transportation costs. In Ecuador, unrest blew up after President Lenin Moreno ended fuel subsidies.

Argentina, meanwhile, is back in the grip of capital controls after voters revolted against President Mauricio Macri’s budget-cutting agenda and handed his opponents a commanding lead ahead of presidential elections on October 27.

The upshot is that Latin Americans are yet again rejecting austerity sought by investors and the likes of the International Monetary Fund, arguing it does little to reduce income inequality or improve social services.

That leaves leaders in the tight spot of needing to cut back yet knowing that doing so is likely to spark political upheaval or even their ouster. While austerity has a history in South America, including by force under military governments in the 1970s, the commodities boom that began around 2000 opened up spending leeway that has now evaporated again.

“Investors excited about the region’s turn to the right were underestimating the challenges,” said Daniel Kerner, Eurasia Group’s managing director for Latin America. “Presidents are caught between the need for adjustments and their inability to put them in place.”

A familiar dilemma

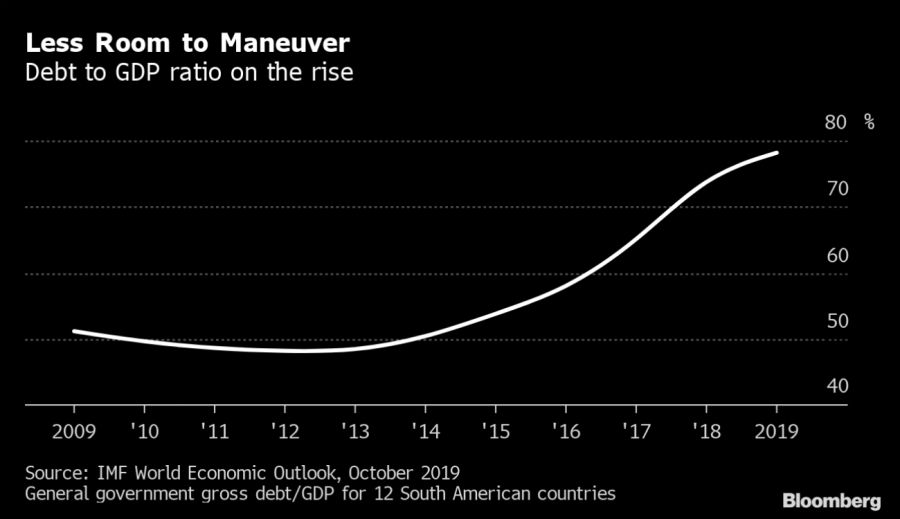

That familiar dilemma for the region’s leaders is sharpened by the end of the commodities boom, slowing growth and rising government debt, which jumped in South America to an estimated 78 percent of gross domestic product this year from 51 percent a decade ago, according to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Investors are already pricing in the return of political risk. While each country has specific flash points, the likely outcome in each case is eroding government support for a pro-market agenda and less stamina to rein in spending.

Chile, where a growing wealth gap has left many citizens struggling to get by, may be the most jarring case. Piñera’s retreat on Saturday failed to immediately halt looting and riots, which prompted the first state of emergency since General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

“Reforming the economy is tough -- you can win the argument and lose the elections,” Chilean Finance Minister Felipe Larraín said in Washington just before violence erupted in his country over the weekend.

In Argentina, Macri is under pressure after being trounced in a primary on August 11. That was enough to trigger a historic market sell-off, leading the government to reimpose capital controls and unilaterally push out debt maturities.

Presidential contender Alberto Fernández has promised relief, suggesting Argentina may be headed for a renewed populist turn that could unwind economic reforms and push the country toward renegotiating its debt.

His running mate, Christina Fernández de Kirchner, is the standard bearer of Juan Perón’s legacy and oversaw what became a closed-off economy during her two terms as president.

Tackle inequalities

Latin America’s tensions played out as finance chiefs concluded the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington over the weekend.

“There is a clear sense that it is important to assure some sort of economic development that also tackles inequalities, which may get amplified in a moment of global slowdown and trade uncertainties,” Mexican Finance Minister Arturo Herrera said during the meetings.

Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean is expected to slow to 0.2 percent this year from an average 0.6 percent in the previous five years, according to IMF data.

For all the market shocks, Latin America has a history of exploding unrest when prices go up for essential services and products, which are often subsidised and subject to price distortions.

In 2013, a bus-fare hike in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro set off Brazil’s biggest protests in more than two decades and shook politics in the region’s biggest economy. Last year, truckers went on a paralyzing strike after increases in the diesel prices.

Challenges to government authority

Other challenges to governments’ authority aren’t helping.

Mexico’s struggle to exercise state control were on display last week when President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s government ordered the release of the son of imprisoned drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán after cartel members overpowered Mexican forces. In Venezuela, more than 4 million people have fled hunger, political repression and a dysfunctional economy under Nicolás Maduro.

It all suggests an array of risk factors with no quick solutions.

“In almost all of South America, we have unpopular governments with fiscal problems facing angry voters tired of corruption, bad public services and the lack of economic dynamism,” Eurasia’s Kerner said.

--Bloomberg

Comments