Is it realistic to aspire to a relationship of equals with China? Is there a method for Argentina to develop a win-win situation? Or is the economic asymmetry with the Asian superpower necessarily conducive to a centre-periphery model? And in any case, what can be done, if not to eliminate it, to reduce such disparity?

The obvious reference point in understanding the growing ties between Argentina and China is the historic relationship our country has had with last century’s great power, the United States. The issue is whether we can write a new story, this time with China. One which does not involve a “carnal” relationship nor us becoming another “backyard.”

The Chinese government swears the contrary. It promises Latin American countries will enjoy “equality”, “mutual respect”, “reciprocal benefits” and “shared gains.” It says China and our region are in the same phase of development and, as such, we share common objectives into the future.

China is Latin America’s second-largest trading partner, and Latin America is the second destination for Chinese exports. In 2017, trade between both parties reached US$ 270 billion. There are 2,000 Chinese companies currently operating in the region.

But what are the pillars of this relationship? Latin America has a trade deficit of more than US$60 billion with China. Seventy percent of exports to the Chinese markets consist of soy, minerals and hydrocarbons. Chinese purchases of Latin American assets consist more of primary commodities than in other parts of the world. And the financing rates that China offers to Latin American countries are quite high.

“Today, the relationship is completely asymmetrical and it has been defined for some decades by a centre-periphery model: we export primary commodities to China and we import their manufacturing,” says Eduardo Oviedo, a local China expert at the CONICET research body and a professor at Rosario National University.

“With the exception of countries like Brazil and Chile, which have achieved a surplus (with China), we are in a very unfavourable situation,” Oviedo adds.

XI JINPING VISITS

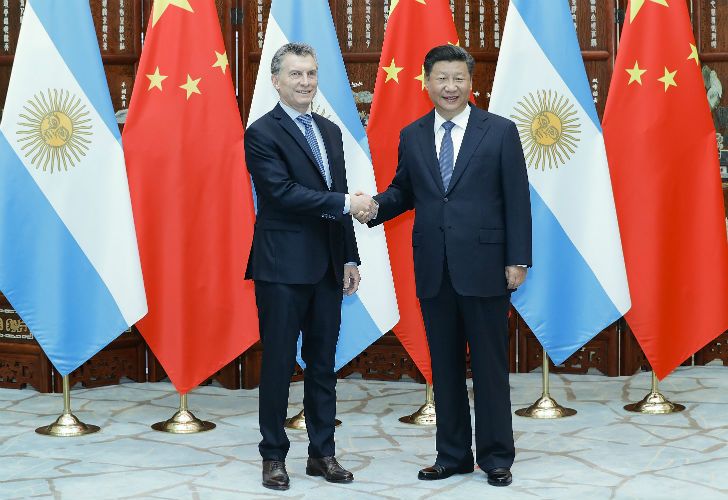

The dynamics of the relationship are conditioned by the region itself. The Argentine government must keep this in mind in the coming days with the arrival of Xi Jinping to the G20 Leaders Summit in Buenos Aires, where he will meet with his Argentine counterpart Mauricio Macri.

The Chinese hope the presidential visit will instigate a sort of relaunching of the relationship with Macri after tensions in 2016 and 2017 which began calming down over this year.

The Chinese ambassador to Argentina, Yang Wanming, said last Friday that both heads of state will this Sunday sign “an action plan” to guide the relationship into the next five years. It will reportedly include billion-dollar investment and infrastructure deals.

Among other points, the agreement will formalise a currency swap between the central banks of both countries, which had been agreed to during Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s presidency. The amount in the Chinese Yuan equates to US$8.5 billion, which adds to an existing US$11 billion.

In the area of trade, it will also remove a double taxation mechanism affecting businesses. An agreement will also be signed to increase Argentina’s presence on Chinese electronic trade platforms. And the two countries will agree to opening new markets for Argentine goods, including beef, lamb, honey and cherry exports.

These measures align with others taken throughout 2018 like the total opening of the Chinese market to Argentine frozen beef exports, with and without bone, which was finalised last May following 15 years of negotiations; and the announcement that China would again buy Argentine soybean oil after a 13-year absence.

Argentina has an annual trade deficit with China of US$5 billion. In the last few months, Beijing has made several gestures of trade flexibility toward our country.

The problem has been that Argentine companies have not known how, or not wanted, to make the most of this opportunity. At least according to Argentina’s Ambassador to Beijing, Diego Guelar, an influential player in Macri’s foreign policy agenda and a major defender of liberal trade policies with respect to China.

“We keep repeating the protectionist argument here of companies which have a concentration of supply in our domestic market”, Guelar said. “But a fear about China is mythological and we should banish it. If one looks at Peru, Chile, Brazil, Paraguay... they all have a surplus with China. The Chinese market is open. The problem is on our side. We neither produce nor offer enough to make the most of [China’s openness]”.

INTERESTS

China’s major interest in Argentina, however, does not lie in trade. Beijing is planning several multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects in our country in the coming years. The best known among these is the Cóndor Cliff hydroelectric dam (formerly known as the Néstor Kirchner dam) and the Barrancosa dam (formerly Jorge Cepernic) in Santa Cruz, financed with US$4.3 billion worth of Chinese capital.

The projects were put on the back burner after Gerardo Ferreyra – who was close to the Kirchners – was arrested in connection with corruption allegations stemming from the so-called “notebooks” or “cuadernos” graft investigation. Ferreyra is the owner of Electroingeniería, the local partner firm of China Gezhouba Group, which is in charge of the projects.

When Macri took power in 2015, he almost withdrew Argentina from that deal but then-foreign minister Susana Malcorra convinced him that it would be unwise to fail the Chinese government, which controls and funds Gezhouba’s activities. He opted for demanding the construction consortium to revise certain clauses in the contracts and carry out an environment impact study.

In the end, there was agreement and mid-way through 2017, the government gave the green light. Works started in last March but were suspended again following Ferreyra’s arrest.

“Chinese companies frequently associate with companies close to the government of other countries to better position themselves in tender processes,” a Chinese official with access to the Argentine government said. “The problem is when the government changes.”

The Chinese now hope that Macri will guarantee the continuity of the project. The idea is to develop a plan without Electroingeniería that allows the project to continue towards providing Argentina an annual saving of US$1.2 billion worth of energy imports.

China is also pushing negotiations to construct a nuclear energy centre in southern Neuquén province using its own technology. President Mauricio Macri’s administration had expressed interest in the project but talks were bogged down amid contrasting opinions from the Treasury Ministry and Energy Secretariat. Economy minister Nicolás Dujovne’s office considered the idea inopportune in light of the government’s austerity agenda, including in the area of public works.

INTERPRETATIONS

Critics of the “Chinese landing” in Latin America say Beijing is seeking to hand off its excess installed capacity to other countries. The infrastructure contracts usually involve taking on Chinese material, labour and know-how.

They also warn about elevated debt risks for countries which take Chinese financing at high rates. This has been the case in some countries in Asia and Africa.

Beijing rejects these suggestions and attributes such fears to two causes: the supposed scare campaign on the part of the United States because of its fear of Chinese expansionism; and erroneous Western “perceptions” about the Chinese development model.

Beijing has identified these “stereotypes and prejudices” as one of the major obstacles in its relationship with Latin America; and proposes to eliminate them by force through greater cultural exchange.

In any case, Washington has good reasons to worry about the expansion of its biggest rival in what was traditionally Washington’s greatest area of influence.

In the midst of a ‘trade war’ between both countries, China is fighting to gain extraterritorial presence in strategic areas of energy and defence. Argentina is part of that strategic dispute. Take, for example, what has happened at the lunar observatory base in Neuquén, which was built with Chinese capital, with the capacity to monitor satellites. Though it is supposed for civil use, the Donald Trump administration has expressed to Argentina its concerns that China may use the base for military purposes.

The Argentine government needs to keep this tension in sight. Until now, the Macri administration’s policy approach to China has been “erratic”, according to some officials at the Foreign Ministry.

For the Chinese, the relationship with Argentina is part of a longer game. To make the most of it, we must learn how to play.

*Facundo F. Barrio is the chief international affairs reporter at Perfil

See also: Government caught in middle between US-China trade row

Comments